Legendary hockey reporter Stan Fischler writes a weekly scrapbook for NHL.com. Fischler, known as "The Hockey Maven," shares his humor and insight with readers each Wednesday.

This week is a treat to three of the most off-the-wall episodes involving hockey players. These include Hockey Hall of Famers Ching Johnson and Frank Boucher to third-line skaters like Fern Gauthier, who made good on a bet that he could shoot the puck into the ocean from an adjoining Atlantic Ocean pier.

THE RANGERS HIJACKED TROLLEY CAR GAMBIT

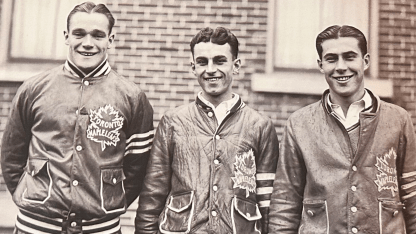

Can you imagine a couple of future Hall of Famers "borrowing" a Toronto streetcar when they were locked out of their training camp hotel. It happened in the fall of 1926 when the New York Rangers, preparing for their first season in the NHL, were boarding first at Toronto's downtown King Edward Hotel and then the Peacock on the outskirts of Canada's Queen City.

Rangers defenseman Ching Johnson and center Frank Boucher were the last players dining at the King Edward when they realized that it was almost curfew and the team had moved to the Peacock Hotel on the outskirts of town.

"Around 11 o'clock, that evening Ching and I remembered that we'd been instructed to check out of the King Edward and report to the Peacock Hotel in West Toronto not far from our practice rink." Boucher wrote in his autobiography, "When the Rangers Were Young."

"But by the time we got to the Peacock we found that we had been locked out, so we decided to take a streetcar back to the King Edward and stay there for the night."

They added a flask of "refreshment" to sustain them on the trip downtown. Suddenly, a trolley car lumbered down the tracks, empty except for the motorman. The two Rangers boarded the streetcar and immediately offered some "refreshment" to the driver.

"When an occasional citizen advanced to climb aboard, the motorman grandly ignored him, cruising along on our nonstop express," Boucher said. "As he roared east, he advised us that his route did not pass the King Edward.

"But Ching cheerily recalled that the tracks did. With that, the motorman leaped out, changed the switch, and we sailed down dark streets, clanging the bell happily until we drew up in front of the King Edward. The motorman had taken us miles out of his way and accepted no fare."

But Johnson was livid when they entered the hotel lobby.

"Frank, that dirty rat," he snapped to his trolley-abducting buddy, "the motorman stole my jug!"

THE GUY WHO COULDN'T SHOOT THE PUCK IN THE OCEAN

You must have heard the expression dozens of times about a slumping shooter:

"He couldn't shoot the puck into the ocean if he was standing at the shore."

But how many times has a victim of such a hockey insult been able to disprove -- or prove -- the theory?

Well, it happened to one NHL player, Detroit Red Wings forward Fern Gauthier. During the World War II years, the native of Chicoutimi, Quebec, had been a productive scorer, first with the Rangers and later with the Montreal Canadiens.

By the time Gauthier wound up in Detroit, his goal totals plunged until the 1946-47 season, when the well virtually run dry. The more Gauthier skated, the more it was hard to believe that he once had scored 14 goals for the Rangers and 18 with the Canadiens.

After a while around the Detroit clubhouse, he became known as the Red Wing "who couldn't put the puck in the ocean." Soon the jibe began spreading around the six-team League and Rangers press agent Stan Saplin picked up on it.

"In no time at all it became kind of a League joke," Saplin said, "but Fern took it good-naturedly."

Meanwhile, Detroit Times hockey writer Lew Walter decided to get in on the act and eventually the paths of Walter, Saplin and Gauthier would cross, thereby creating a mini hockey legend.

"Lew got to thinking about all the ribbing," Saplin remembered, "and he realized that it was unfair in Detroit to say that Fern couldn't put the puck in the ocean since Detroit was hundreds of miles from such a body of water.

"One morning, though, when the Red Wings checked into a New York hotel prior to a game with the Rangers, Walter picked up the phone and arranged for a photographer to meet him. Then he phoned Gauthier and gave him certain instructions."

Saplin was informed of the grand scheme, as were a few New York writers.

"Within an hour," Saplin recalled, "Walter, the photographer and Gauthier -- carrying a hockey stick and a handful of pucks -- were on their way downtown. They headed for the Battery at the tip of Manhattan. There the photographer would get the proof on his film to disprove, once and for all, the false legend."

Just to be sure that the evidence was well-weighted on Gauthier's side. a few Detroit players were invited along to act as additional witnesses.

"We took along Gordie Howe, Ted Lindsay and Marty Pavelich," Walter said. "They were able to refute the first two 'supposed misses' made by Gauthier."

One apocryphal version had it that Gauthier had missed on his first two attempts.

"It was said," Walter laughed, "that as Fern shot the first puck, a seagull swooped down and snatched it and then, as a second puck went sailing out, a tugboat came chuffing by with a string of barges, on one of which the puck landed."

Both Saplin and Walter insist that Gauthier was able to shoot puck after puck into the Atlantic Ocean and he was just delighted to go along with the sight gag.

"Fern proved," Walter concluded, "not only that he could put the puck in the ocean, but also that he was a good sport by entering into the spirit of the rib. He was a winger of great potential, of fine personality, and if injuries had not hampered him, might have made a true success of pro hockey!"