Like many kids, 10-year-old Zakhar Dorozhenko of Scottsdale, Arizona, has a poster of his idol on his bedroom wall. It's a colorful image of Auston Matthews in his Team USA uniform. It's even personalized with a note from Matthews, thanking Zakhar's father for his role in his success.

Boris Dorozhenko started working with Matthews on a full-time basis in 2006, before Zakhar was born. Matthews, 8 at the time, was learning the game he would one day come to master.

Hockey in Arizona heating up

Success of Auston Matthews, presence of Coyotes growing sport in Southwest

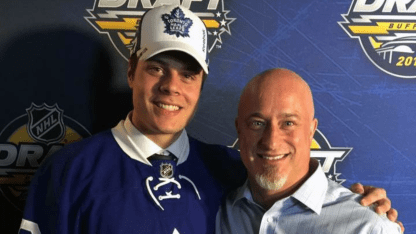

Brian Matthews, Auston's father, met Dorozhenko, a Ukrainian-born hockey pro with a unique method of training focused on skating and balance, at a skating camp. Dorozhenko was living in Mexico at the time and at the elder Matthews' urging, Dorozhenko moved to Arizona to work with Auston and start his burgeoning business, Next Generation Hockey schools. Ten years later, Dorozhenko's pupil was chosen first in the 2016 NHL Draft, selected by the Toronto Maple Leafs.

Matthews' rise to the top of the hockey world changed things for Dorozhenko and his business, with parents now wanting him to turn their son into the next Auston Matthews. Matthews' stardom also changed things dramatically in Arizona, where ice hockey players are starting to become almost as commonplace as cactuses.

"My son just became a hockey player two years ago and a lot of his interest is because of Auston Matthews," Boris Dorozhenko said. "He wasn't really big into hockey before; now he's begging me to go practice. We put this poster in my son's room and something changed. Now he's looking at me with the same eyes as many parents who say, 'Hey, can you please do with our boy the same things as you did with Auston Matthews?'"

Dorozhenko laughs as he speaks in his heavy Ukrainian accent. If only it were that easy. It's not. Matthews is a prodigy who is as much the face of hockey in Arizona as he is the face of the Maple Leafs.

Watch: Boris Dorozhenko discuss the Next Generation "Innovative Hockey Schools" on YouTube

Matthews is the kid who was influenced by the Arizona Coyotes, attending games with his uncle, getting hooked and relentlessly pursuing the thing he enjoyed most. He's the kid who spent countless hours playing 3-on-3 hockey on synthetic ice, honing his puck handling skills. He's the kid who begged his coaches to go on the ice with the older kids just because it meant more time on skates, more time to practice.

"All those years he played for me, he was always asking to go on the ice," said Ron Filion, one of Matthews' former coaches and the founder of the Arizona Bobcats youth program. "I've never seen a kid who wanted ice time as much as him."

Matthews will be back on Arizona ice on Dec. 23, when the Maple Leafs visit the Coyotes at Gila River Arena. When he plays a game in Arizona for the first time as an NHL player, Matthews will find a community emboldened and motivated by his success, determined to shine in the spotlight he has put on it.

"People knew we were here and it was good," said Corey Hirsch, a former NHL goalie and current Scottsdale resident. "But Auston Matthews, he's changed it all."

Matthews' impact might be felt for decades to come.

"It's just now that everybody is starting to talk like, 'Holy cow, hockey in Arizona,'" said Steve Sullivan, a former NHL player and current director of player personnel for the Coyotes. "That's been happening for the past 12 months. We're going to have to give that seven to 10 years to see fruition of it."

There are 7,510 players in Arizona registered through USA Hockey, including more than 3,800 youth players (18 years old or younger). Thanks to Matthews, they have an idol that came from their backyard.

And that's the beauty of Matthews' rise to the NHL: He isn't any different than the kids who idolize him now.

He's from Scottsdale. His dad played baseball, just as Matthews did until hockey became his full-time passion. His mom, Ema, is from Mexico. He has an older sister, Alexandria, and a younger sister, Breyana. By all indications, the Matthews are regular people.

The only difference is Auston, "Papi" as he's known at home, developed an extraordinary talent through hard work and determination. He did it without leaving Arizona for cooler temperatures and more opportunity. He did it under the watchful eye of kids across the region who are growing up in the same programs that helped produce the No. 1 pick in the NHL draft.

"It was all pretty normal for me growing up," Matthews said. "I don't look at it any other way. Everybody has different routes, different ways to get to the same place. Obviously mine was a little different growing up where I grew up, but to me it was just normal. I was playing hockey every day, having fun, enjoying the game."

Now he's a celebrity.

"Auston, in our program, he's a god," Filion said. "We have 170 kids in our program and I think every family has bought a ticket for when Toronto comes to town."

That's just one example of the tangible results Matthews already has produced for his community and its local NHL team.

Hirsch, whose son, Hayden, plays in the Phoenix Jr. Coyotes program, the largest youth program in the state, said his summer goalie school struggled to fill up last summer because of the influx of hockey schools in the area. It typically sells out in less than a month's time, according to Hirsch.

"There is just a mad flood of everybody trying to find the next Auston Matthews here, that one gem and that one diamond," Hirsch said. "It wasn't a good thing for me, but it shows you that there are a lot of schools now, a lot of people coming into the market now. Now it's not a secret."

Arizona Coyotes co-owner, president and CEO Anthony LeBlanc said ticket sales spiked after Matthews scored four goals in his NHL debut on Oct. 12. It didn't matter that he scored them for Toronto.

"You could see on social media that Auston Matthews went to the top of the list in Phoenix trends, but then our sales department saw a significant uptick in people buying tickets in general, as well as the one home game that we have when the Maple Leafs are in town," LeBlanc said. "People were excited about hockey. It's really helped the awareness."

Matthews turns shy when the topic of his fame and influence is raised.

"To me it's a pretty big honor to just be a part of that growth in Arizona," he said. "A lot of kids are starting to play and they're growing the game so well. It's going to be awesome to see the growth there in the next five to 10 years."

If it's anything like the growth in the previous 20, there may be another player like Matthews to come soon.

Coyotes connecting to the community

Despite a warm-weather locale and 15 sheets of ice available throughout the state, Arizona ranked 19th among USA Hockey's 52 districts in total player enrollment for the 2015-16 season.

The numbers are even more staggering when viewed through the prism of the presence of the Coyotes, who are celebrating 20 years in the Valley of the Sun this season.

Total Arizona enrollment in USA Hockey has increased 220 percent (2,349 to 7,510 players) from 1996, the Coyotes' inaugural year after relocating from Winnipeg, through the end of last season. The percentage of players 18 years old and under was up 180 percent (1,357 to 3,803).

This growth, in many ways, is a credit to having the Coyotes in the market. They are, after all, a big reason Auston Matthews fell in love with hockey. Without the Coyotes, Matthews might be a solid baseball prospect playing in the minor leagues or at the NCAA level. Maybe he's just a college student now.

© Christian Petersen/Getty Images

"I think the Coyotes and USA Hockey have done a great job promoting it and growing the game," Matthews said.

But past ownership issues plagued the Coyotes and blunted some of the growth. The current ownership group, which took over the franchise three years ago, is changing that. It has been supportive of the youth game.

"The new ownership has really been involved; before that it was pretty much zero," Filion said. "It was buy tickets, we'll see you there. Now there is an involvement, a big effort."

LeBlanc said the Coyotes are involved in numerous grow-the-game initiatives and recently announced plans to build an outdoor street hockey rink at Luke Air Force Base in Glendale, the first of what they hope to be many in the area.

"Our view is it might be difficult to get kids on ice, but at least we want to get sticks in their hands and get them understanding what the game is all about," LeBlanc said.

The Coyotes extended their footprint south to Tucson this season, relocating their American Hockey League team there and renaming it the Tucson Roadrunners. The only ice sheet in the city is at the Tucson Convention Center, home of the Roadrunners. Yet, Tucson has experienced its own surge in players.

Tucson's Wildcat Youth Hockey Association started with 15 players in the 2011-12 season and is now up to 85 registered through USA Hockey with approximately 100 more in a separate Learn to Skate program and 50 more registered for a Learn to Play program through the NHL and the Coyotes, according to Ryan DeJoe, the organization's coaching director.

"[The Coyotes] are starting to get some traction at these lower levels," said Mike O'Hearn, president of Coyotes Ice LLC, which oversees Ice Den rinks in Scottsdale and Chandler. The Scottsdale rink serves as the Coyotes practice facility. "That's something they quite honestly haven't done for ages."

O'Hearn worked for the Winnipeg Jets for 13 years and moved with the team to Phoenix.

"It's really encouraging to see what's happening now, that they're really putting a focus and appreciating and understanding the importance of digging into the communities," O'Hearn said. "It seems like such a simple thing to think about and why wouldn't that be first and foremost, but obviously they had a lot of challenges that faced them and these things seem like small potatoes against the bigger problem, like if they were going to stay in the Valley. It's important to stress that they have really taken the bull by the horns here in recent times.

"We have a tremendous relationship."

The relationship is easier to have when the Coyotes players are as visible as they are. Captain Shane Doan is on the ice at the Ice Den Scottsdale working with his son Josh's U-14 team in the Jr. Coyotes program on most off nights.

Dorozhenko said Coyotes goalie Mike Smith recently joined in on a skills session he was conducting.

"Happens all the time," Hirsch said. "When I grew up in Calgary, if I saw a Flames player it was at a hockey game or at an autograph signing. That was the only time. They never came out to your practices. You never saw them."

The next phase is for the Coyotes to start winning.

Matthews remembers going to 2012 Stanley Cup Playoff games at Gila River Arena when the Coyotes reached the Western Conference Final. The atmosphere, the "Whiteout" crowds, were unforgettable.

"That was a pretty exciting time for a lot of kids watching, especially for myself, going to those games and seeing a packed arena, which you don't see often down there," said Matthews, who was 14 at the time. "I remember going to those games and watching those physical, fast matchups."

Arizona is rebuilding now with young players in forwards Max Domi, Anthony Duclair, Dylan Strome and defenseman Jakob Chychrun. Defenseman Oliver Ekman-Larsson already is a star and a potential Norris Trophy contender.

© Christian Petersen/Getty Images

"Some of those young guys we have here now are amazing, and my son knows every one of them," said Mike DeAngelis, director of hockey for the Jr. Coyotes Elite AAA program. "He's an Arizona-born kid watching the Coyotes on TV and a lot of these kids, his friends, want to be like them, to be like Domi and Duclair."

The Coyotes have the youngest general manager in the NHL in 27-year-old John Chayka, who analyzes the game in new and different ways, including the use of several advanced metrics. Dave Tippett is the veteran coach trying to weave it all together.

On Nov. 14, the Coyotes announced preliminary plans to partner with Arizona State University to build a new 16,200-seat arena with an adjoining 4,000-seat multi-purpose arena in Tempe. Hopes are the building will be complete in time for the 2019-20 NHL season.

The Coyotes feel a move to the east side of the Valley, where the majority of their fan base is located and where most of their players live, would be a boost to the organization. The current home of the Coyotes is in Glendale, more than 20 miles from Tempe.

"It's huge," Matthews said. "It'll be an easier commute for all the kids that want to go. It's only a 20-minute drive from where I'm from versus a 50-minute drive to Glendale."

Arizona State University Effect

If the arena plan goes through, it'll be another boost to the Arizona State University program, which for kids like Zakhar Dorozhenko is a new option.

ASU became an NCAA Division I hockey program last year. It's one of two Sunbelt schools with Division I hockey programs. The other is the University of Alabama-Huntsville, which produced Edmonton Oilers goalie Cam Talbot.

"I know my kid is talking about it already and that was never on the radar screen," Coyotes broadcaster and former player Tyson Nash said of his son, Ty, who is 13. "This is Division I hockey and you can get your education and enjoy that campus and the sunshine, the pool, the barbecues and the girls. Oh my goodness, where do you sign up if you're 18 years old?"

ASU is luring players from Western Canada and U.S. hockey hotbeds such New England, Minnesota, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin, as well as Russia and Sweden. Perhaps most importantly, there are three players on the roster now from Arizona.

© Richard T Gagnon/Getty Images

Defensemen Drew Newmeyer and Edward McGovern are from Scottsdale. Forward Anthony Croston is from Phoenix. In addition, one of ASU's top commitments for the 2017-18 season is Johnny Walker, who is from Phoenix and is currently playing for the Chicago Steel in the United States Hockey League.

Arizona has become a legitimate recruiting base for ASU, Sun Devils coach Greg Powers said.

"It's absolutely a huge priority for us to keep the very best kids from our state at home, play for their hometown school, to help us build this program and build a tradition with homegrown kids because there are some really good ones out there," Powers said.

Arizona State didn't actively intend to become a Division I program, Powers said. It happened organically.

The Sun Devils built a successful club program and won the American Collegiate Hockey Association Division 1 national championship in 2014. ASU's success made it a destination for players looking to transfer out of Division I programs because of a lack of playing time or off-ice reasons. It became a destination for junior hockey players looking for all the fixings of a college program, plus good weather.

"Our last club year [2014], we had seven kids from the USHL and Division I transfers, we won a national championship and we went to Penn State and beat their NCAA team," Powers said. "What we did was focus on what was right in front of us and throughout that process gained the support and belief of the right people, donors and administration, and basically they said, 'Look, I think these guys can do it at the highest level, so let's give it a shot.' We just became elite at our level to the point where everybody garnered the attention and belief we could do it at the next level."

ASU wants to be the model for other Pac-12 schools to follow, most notably the University of Arizona.

"We have had lots of people ask us about [hockey] since the news came out that ASU is having it," University of Arizona athletic director Greg Byrne said. "We're needing to fund the programs that we have right now and address the improvements we need to continue to make there and that's where our focus is. We don't have any plans for it at this point."

© Richard T Gagnon/Getty Images

Powers isn't deterred. He knows others are watching. The University of Colorado, University of Utah and University of Arizona are ranked in the ACHA Division 1 Top 25. Maybe one of them will be the next Pac-12 school to go Division I in hockey.

"It's of the utmost importance to us and everybody at our university to do this the right way so in a decade we have Pac-12 hockey," Powers said. "That's our goal."

It could get better for the Sun Devils if the new arena in Tempe becomes reality.

ASU splits its home games between Gila River Arena and Oceanside Ice Arena, a public facility in Tempe that received a $300,000 renovation from the university so the hockey program could have a pro-style dressing room and training room. The new arena would allow the Sun Devils to play all of their home games close to campus.

"I know everything being discussed sounds incredible and the sky is the limit with the potential of that coming together," Powers said. "We're partnered with the Coyotes now because they're sharing their venue with us and they've been incredible with us. If this ends up coming to fruition, clearly it's a dream scenario for everybody."

A community of pros

Matthews' undying desire to be on the ice, to learn, to train, to practice his craft led him to the top of the 2016 NHL Draft and to the NHL. He wouldn't have gotten there without the quality coaching he received in the Valley from many recognizable people.

"Claude Lemieux was my coach for a little bit; Jeremy Roenick was there," Matthews said, referencing the two former NHL players. "A lot of guys. Ron Filion was my coach. He didn't play in the NHL but he played major junior and pro in Europe. I'm fortunate to have a lot of those guys help me."

The same thing is happening now at an even greater volume in rinks across the state. Former NHL players, many who played for the Coyotes, have moved to Arizona for sun and warmth and are blowing whistles, conducting drills, running benches, molding the players and driving them to live up to professional standards.

Sullivan, Hirsch, Nash, Ray Whitney, Sean Burke, Derek Morris, Dave Ellet, Shawn McCosh, Greg Adams, Dave Scatchard, Wayne McBean and Keith Carney are among the many former NHL players, many of them Canadian, who are coaching in the state.

"You can walk into any rink around the world and I can guarantee you won't see what you see at the Ice Den in Scottsdale," Nash said. "It's crazy the coaching that these kids have and who they are learning from. We all grew up playing hockey learning from a dad who was happy to volunteer, rah-rah-rahing you. These kids are learning from NHL players."

It extends to girls hockey too. Nash said his daughters, Maddie, 15, and Georgia, 11, each have former professionals coaching them. The same for Powers and his 9-year-old daughter, Isabel.

"Girls hockey is growing and it's just fun to see," Nash said. "You couldn't find kids to make up a team before and now we've got choices to make, which is great."

The pros are impressed with the surge of talent in the area, despite a lack of depth that still exists.

"Our depth ends at like 10 or 11 skaters that can really compete, but we do compete nationally," DeAngelis said. "We're not knocking off Detroit and Boston, but we certainly don't get blown out. I would say a typical game would be 4-2 or 5-3. We never were like that 10 years ago. The kids weren't good enough 10 years ago to go outside the Arizona borders and compete against the elite level kids around the country. A lot of that has to do with there are many ex-NHL players who live here and have turned into coaches. The level of training these kids in Arizona are getting, in my opinion, rivals anything you can get in North America."

Future growth

A player like Matthews might never come out of Arizona again, but developing hockey players who can advance in the game, play collegiately or in major junior hockey and potentially get drafted is becoming an annual occurrence in Arizona.

Todd Burgess, a Peoria native, was drafted in the fourth round (No. 103) by the Ottawa Senators in June. Scottsdale's Austin Carroll was a seventh-round pick (No. 184) of the Calgary Flames in 2014 and is playing for the Stockton Heat in the AHL.

The Western Hockey League has averaged between three and five Arizona players on its rosters during the past five seasons, according to a WHL spokesperson. Five Arizona players are in the USHL this season, including Erik Middendorf, who plays for the United States National Team Development Program's U-17 team.

Middendorf, whose uncle is former NHL player Max Middendorf, is committed to play at the University of Denver.

Scottsdale's Ryan Savage, the son of former NHL player Brian Savage, is committed to play Division I hockey at Miami University of Ohio.

Former NHL player Ulf Samuelsson's sons Henrik, Philip and Adam all went through the Arizona youth programs. Philip, 25, is in the AHL with the St. John's Ice Caps, Henrik, 22 is a Coyotes prospect, playing for the Roadrunners. Adam, 16, is teammates with Middendorf in the USNDTP.

© J McIsaac/Getty Images

"At our facility we have a Wall of Fame and that wall continues to grow every year with kids playing major junior and college," DeAngelis said. "The Auston Matthews situation is such an outlier situation that knocked everybody over because it happened so fast, but the slow growth of talent is happening every year."

It has become increasingly difficult for the community to keep up with the demand. There are 11 sheets of ice in the Greater Phoenix area and 15 in the state. Filion said they need at least four more sheets in the Valley alone, especially with the numbers that are showing up in Learn to Play and Learn to Skate programs.

"Obviously it starts from the ground up, but right now we can't really start from the ground up with new kids because the ice is not there even though the want is there," Filion said. "Whoever would build a new sheet would have to be patient because the kids who are already peewee, they're going to stick with their program. But with all the kids that are trying to come in there is going to be a possibility for more growth."

More ice could bring the cost down for families who want to get involved. It costs $400 per hour to rent ice at the Ice Den in Scottsdale. It could cost a family with one player more than $1,500 per season, before factoring in travel, Nash said.

The Coyotes hope their new arena with ASU solves at least part of that problem, because it means adding two new sheets in Tempe.

"That's how you grow the fan base and get more youth," LeBlanc said. "When I talk to my colleagues that operate the San Jose Sharks or the Dallas Stars, that's really been the biggest thing for them, the growth of the game, getting more ice sheets."

The difference between those markets and Phoenix is only one has produced a No. 1 pick.

"I remember when I was 7, 8 years old, there was only one team, one group of guys that were good hockey players and played together," Matthews said. "As we got older we started playing for different teams and we went our separate ways, but by the time we were 15 or 16 there were so many different teams and all of us were spread out. It made for some good competition. It's even moreso now that there are teams at so many different levels.

"It's just continuing to grow."