ST. CATHARINES, Ontario -- Wild coach Bruce Boudreau played professional hockey for two decades. He spent much of that time in the minor leagues; Boudreau played in 141 NHL games.

Without the "big" paychecks of the NHL -- which, by today's standards, weren't very big -- players like Boudreau needed to find a second job during the offseason to make ends meet.

Not wanting to work "a real job" outside of hockey, Boudreau hatched an idea with Maple Leafs teammate Rocky Saganiuk: They'd start their own hockey camp.

Early Struggles Didn't Deter Boudreau's Dream for Hockey School

After inauspicious start, camp has become highlight of many summers

So, in 1982, the very first Golden Horseshoe Hockey School took place. And while the location has changed, the institution has not. Each year, during the first full week in August, hundreds of families from all areas of North America head to this corner of southern Ontario for seven days in hockey heaven.

When searching for a title for the camp, Boudreau didn't want to use his surname. So they chose "Golden Horseshoe," a nickname by locals given to the horseshoe-shaped area of Canada stretching from Toronto, around the western shore of Lake Ontario to Niagara Falls -- an area that holds more than a quarter of the country's population.

Boudreau and Saganiuk handed out brochures and hung posters in local rinks. And thanks to a sponsorship with an area radio station, that allowed them to air commercials for the camp. About 150 participants were signed up and ready to go on the first day.

The only problem was they had no one to help run the camp.

"We didn't have a clue what we were doing," Boudreau said. "We didn't have counselors; we didn't have anybody until about a week before."

The two turned to Brian Papineau, the Leafs' equipment manager. While Boudreau and Saganiuk ran all of the on-ice instructionals, Papineau handled everything off of it.

It wasn't easy in the beginning.

The first camp was at a rink in a relatively unsafe neighborhood; outdoor activities for campers were out of the question. And while the arena had two sheets of ice, only one was operational in the summer.

Nevertheless, the group made it through.

The dry sheet was used as a ball hockey area, the concourse for Olympic-style games and competitions.

A 27-year-old with no children at the time of the first camp, Boudreau said he wasn't sure how he was able to manage that many youngsters all at once.

"Thirty-five years later, I still don't know how it got done. I really don't," he said.

Crystal clear

For the first few years, Boudreau's hopes of founding a hockey camp empire seemed fleeting. Back then, the camp didn't have things like sponsored lunches, so the price for that came out of the profits. Ice time and instructors weren't cheap, either.

"In all reality, we probably should have folded up the tent," Boudreau said. "But once it started going and we got into the rhythm of knowing how to do things properly, then we started to make a little money and it became pretty well known all over."

Perhaps it's no coincidence that around the time the camp became a money maker, Bruce began dating Crystal.

The couple began their relationship in 1990, and Crystal came to her first hockey school in 1991, a little shy and not sure what to expect.

By 1992, she had taken charge of almost all of the hockey school's administrative aspects.

"I just asked him, 'Do you want me to do this or not?'" she recalled. "I told him I was going to upset some people. I'm a little OCD."

Sure enough, Boudreau's camp became one of the most organized -- and popular -- in the area. At its peak, Bruce and Crystal were running more than 300 kids through the school, investing two or three weeks at a time.

#mnwild coach Bruce Boudreau does it all at camp, including the grunt work. On his way now to get more Gatorade. pic.twitter.com/54kyjTmuFS

— Dan Myers (@DanMyers) August 11, 2017

Remember when I said Bruce Boudreau does it all? Here he is running the penalty box and scoreboard. Also does a great @mnpaguy impression. pic.twitter.com/LqmF8R96M4

— Dan Myers (@DanMyers) August 12, 2017

"This camp was never really organized until Crystal came around," Bruce said. "Back when I was running it [alone], I was just a fly-by-night kind of guy."

Moving on up

It was during this time that the Golden Horseshoe Hockey School gained an unmatched reputation.

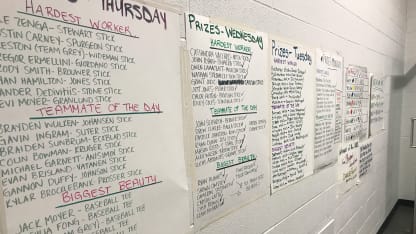

With his coaching career starting to take off, Bruce would beg his plethora of connections for gear to be given away as prizes at his camps: sticks, jerseys, pucks ... anything that his kids would find valuable. As he moved up the ranks, more and more memorabilia flooded in. Soon, it was that plus iPods and mountain bikes and, one year, even cell phones.

"One year, we had 160 electric toothbrushes to give away," Bruce said. "Those things are like 65 bucks each."

In 2014, Bruce and Crystal's final year running the camp before handing it off to several family members (including sons Andy, Ben and Brady), Bruce estimated that more than $100,000 worth of memorabilia had been donated by players, teams and companies, all of it handed out to the kids at camp.

"We would have it all set up the way we wanted it, and the kids and parents would walk in and just go, 'Wow,'" Andy said. "At the end of the banquet, we'd just be packaging things together, a hoodie, a hat, a puck, a stick and just saying, 'Take it.'"

When Bruce Boudreau's sons took over two years ago, things changed. While there is still a mountain of autographed gear that gets handed out, much of it is used to reward players for their on-ice work. Awards for "Best Teammate," "Hardest Worker," and "Biggest Beauty" are handed out daily.

Coming back for more

Over the years, a number of Golden Horseshoe Hockey School attendees have gone on to play professionally, be it in the NHL, the minor leagues or Europe.

Tampa Bay Lightning defenseman Dan Girardi is an alumnus and had his son on the ice this past week. Other NHLers to come through include former Wild forward and current New York Islander Cal Clutterbuck, from nearby Welland, and Detroit Red Wings forward Riley Sheahan, a St. Catharines native.

Girardi dropped by the camp last week, taking pictures with campers and offering advice. Because Girardi has the means and resources to send his child anywhere, Crystal said it means a lot to see him come back and provide his son with the same experience he had.

In many ways, it remains a part of the fabric and charm of the school itself.

"It was fun for them, so they bring their kid," Bruce said. "I know it's fun because the whole idea is fun. But you get on the ice for 21 hours and you're going to improve. Whether you want to or not, you're going to improve.

"I don't believe that in five days, you're going to make a kid into Bobby Orr. But if you let him skate and play and enjoy the game, they can't wait for the season to start when this is done."

Follow the leader

No matter where Bruce Boudreau has coached, youth hockey players from each stop seemed to follow him back to St. Catharines.

When he coached the Manchester Monarchs, the contingent from New Hampshire grew each year.

After moving to Hershey in 2005, the group from Pennsylvania became quite strong. A group from Hershey still makes its way north each year, despite the fact Boudreau hasn't coached the American Hockey League's Bears in a decade.

"It used to be easy, because all the kids that played with Brady would [come to camp]," Crystal said. "As he's grown up, those kids eventually age out of camp, but you'll still get people from there who have heard about the camp [from people who have participated] and want to be a part of it."

Hockey doesn't have as big a following in Washington or in Anaheim, but the number of families from the mid-Atlantic region -- Maryland, Delaware and Virginia -- remains relatively strong.

The Southern California contingent grew again this year with its highest number of participants yet.

In a bit of irony, Minnesota, one of the strongest hockey markets in the United States, has not had the following of other areas. But if history is any indication, it's likely coming.

Bruce even recalled the story of one camper who came all the way from Australia. At the beginning of the week, he could barely skate. Undeterred, he showed up at the rink every day, and by the end of the week was moving around quite well.

At the banquet on Sunday, Boudreau recognized the camper, and every participant stood to give him a standing ovation.

"That was probably one of the most memorable times I've had," he said.

'Best week of the year'

It's "Championship Saturday" at this years' Golden Horseshoe Hockey School, and after a week of drills and off-ice training, the eight teams at camp will finally get to test their skills in a series of games.

The oldest group is on the ice at 8 a.m. sharp. With temperatures hovering around 75 degrees and the humidity on the rise all week, things have gotten dicey in Rink 1 inside the arena.

A group of parents sits in the lobby, peering through fogged up glass at a barely visible hockey game. With the "Swiss Chalet Cup" on the line, the two teams are playing in a fog so thick one can't see the other end of the rink from the other.

Suddenly over the loudspeaker is the crackling voice of a man who owns the best winning percentage by a coach in NHL history.

Sure enough, Bruce Boudreau is manning the penalty box, the controls of the overhead scoreboard in one hand and a microphone in the other.

After each goal, Ben skates over to tell his dad the name of the kid. He then barks it through the microphone throughout the arena.

It's a sight to behold: an NHL coach opening penalty box doors, pushing buttons on the scoreboard and announcing goals over a loudspeaker.

At 62 years old, the 1990s-era scoreboard still presents a challenge. Occasionally, a goal gets missed and Bruce gets a subtle reminder from 19-year-old son Brady, on the ice as a referee.

With plenty on his plate already, Boudreau can't help but do a little coaching as well.

With the youngest group on the ice a bit later, a team in yellow jerseys scores a goal. Before he can even announce its scorer, a team in gray jerseys gets it right back.

"C'mon, we need some defense out there!" he bellows, to the amusement of 50 parents in the stands.

With the grind of yet another long NHL season on the horizon -- what will be his 44th consecutive year either on a professional bench or behind one -- it'd be easy for Boudreau to simply sit by the lake and enjoy his last few weeks away from the rink.

Instead, he spends it in one, and he wouldn't have it any other way.

"It's a part of my summer," Boudreau said. "Some people go on vacations, go to cottages ... we set this thing up and it's the best week of the year, the most fun week of the year.

"It's a lot of work and you're really tired at night, but when you're dealing with the kids and they have a smile on their face, there is a lot of satisfaction."