DETROIT --Ted Lindsay has traveled untold miles through the game of hockey, and every rugged inch of the journey can be found in the relief map that is his face.

There is a magnificent, lived-in quality to this 90-year-old legend's mug. His face is one of craters and deep valleys and meandering scars: imagine the lunar surface painted as a man's face.

Lindsay is fiercely proud of every line that has been richly -- sometimes violently -- earned, each one a souvenir of his take-no-prisoners, 17-season NHL career.

Lindsay on foes: 'I had no friends'

90-year-old Red Wings legend has mellowed … just a little

Read: Lindsay: Everybody was the enemy when I played >>

And yet, softening his facial minefield, one stitched together by an estimated 700 sutures, is a bright, mischievous smile that punctuates a happiness, a sense of "If I had to do it all over again, I'd not change a thing - unless I could be a little meaner still."

We met at Joe Louis Arena Monday afternoon, Lindsay nattily dressed in jacket and tie, carrying three hockey sticks from the Detroit Red Wings dressing room and a red home jersey toted in a colorful "Happy Birthday" bag.

Lindsay had been down the hall harvesting autographed items for a summer golf tournament to benefit his foundation that, since its creation in 2001, has generously supported autism awareness and research. On his left lapel he wore a diamond-encrusted pin that featured the winged-wheel logo of the Red Wings and his No. 7, which since 1991 has hung in the rafters of the Joe.

Over the next hour, Lindsay would talk about his remarkable life, one you couldn't invent today. He spoke of his boyhood as the youngest of Bert and Maud Lindsay's nine Depression-era children in Kirkland Lake, Ontario; the replacement in 2014 of an aortic valve and the insertion six weeks ago of an artery-opening stent near his heart; and the decades of his history in between.

"I loved the game of hockey but I never looked at myself as a great hockey player," he said, the latter claim one that would be laughed at by anyone who saw him play or weathered his fury. "Owners never paid my salary. I always recognized that it was the people in the seats who did. I always wanted to give my best. Some nights, it was great.

"But there were other nights," he added with a laugh, "that I was not too pleased with my performance."

There would be precious few of those during 13 seasons with the Red Wings from 1944-57, three more with the Chicago Black Hawks (as they were then known) after a bizarre trade made by Detroit general manager Jack Adams, to one final season in the sun with the Red Wings in 1964-65, at age 39 following a four-year retirement.

When he finally hung up his skates as one of the most ferocious, feared men in his or any hockey era, Lindsay had won the Stanley Cup four times with Detroit, played 1,068 regular-season NHL games and another 133 in the playoffs, scored 379 goals with 472 assists, won the 1949-50 Art Ross Trophy as the NHL's points leader and racked up a staggering 1,808 penalty minutes - a then-record, and the equivalent of 30 full games.

More than 50 years after playing his last game, he is No. 70 on the all-time penalty-minutes list.

Lindsay listened as these numbers were rattled off, then smiled when I wondered aloud how he'd managed to be that productive offensively given his permanent-resident status in NHL penalty boxes.

"There was no balance because my mind didn't work that way," he said. "Some of the older players on the Red Wings, the defensemen, the veterans, Jack Stewart and Bill Quackenbush, guys like that, they'd say, 'Leave the kid alone, that's his nature, let him unwind when he wants to unwind.' "

An interesting way of describing a one-man wrecking crew.

"That was perfect for me because I hated everybody. I had no friends. I wasn't there to make friends. I was there to win. It wasn't necessary that I score, but I figured I could be an integral part without scoring. I had ability, I had talent and I didn't have an ego that I thought I was great. I realized I had to earn it. That was my purpose - to be the best that there was at the left-wing position. …

"I never looked at stats. I was part of a team. I couldn't do it by myself and nobody else on the team could do it themselves. We were part of a team. I had to help my teammates as much as they helped me. That was my philosophy."

And Lindsay was the quintessential teammate, a player who would roar to the defense of his fellow Red Wings or Black Hawks, whether they needed his help or not.

His battles were legendary. Lindsay didn't merely dislike his opponents, he detested them with every breath in his 5-foot-8, 165-pound body.

"My hatred was sincere," he said of his foes. "I liked to see them dead. That was my problem, I guess. I understood people, understood human nature. I wasn't a psychologist or anything, but I knew people. You'd figure out who the chickens were on the other side, who the bulls were on the other side, [then] spend your time with the chickens and stay away from the bulls."

Which wasn't true, of course. Lindsay was just as willing to mix it up with a bovine as he was with a rooster.

There was no thought, he said, of following in his father's skates. Bert Lindsay was a goaltender in the pre-NHL National Hockey Association and in the Pacific Coast Hockey Association before playing two NHL seasons with the Montreal Wanderers and Toronto Arenas.

One of five boys in the family, Ted Lindsay began skating at age 9 in too-large blades given to him by a Kirkland Lake neighbor. But he'd never be a goaltender.

"No, no," he said with a laugh. "I loved handling the puck, I loved handling that little black thing. I loved hitting people. And I love intimidating people, also."

Lindsay played scholastic junior hockey at St. Mike's in Toronto, and won a Memorial Cup championship in 1944 with the Oshawa Generals. The Toronto Maple Leafs heard of this promising young forward, but Lindsay was hospitalized, nursing a calf that had been punctured in a game, when team brass went to a game, not knowing his name, and scouted the wrong player.

It would be Red Wings chief scout Carson Cooper who later dangled the NHL bait, not even certain whether Lindsay was on Toronto's negotiation list. He wasn't, and fate brought him to the Red Wings, a team he had grown to love - especially hardrocks Jimmy Orlando and Jack Stewart - by listening to powerful WJR radio, whose signal reached Kirkland Lake from Detroit on crisp, winter nights.

"My kind of hockey - big, tough guys," Lindsay said of the Red Wings of his youth. "I got to play with Jack Stewart for many years and I appreciated that. He was a wonderful policeman to have on your team. He was a farmer from Pilot Mound, Manitoba. Marty Pavelich (a close Lindsay friend, teammate and, later, business partner) used to say, 'I'm seven-foot tall when I'm on the ice with Jack Stewart.'

"I've been blessed many times," Lindsay said both of his life and of being discovered by the Red Wings. "I've never thought it was fate, but maybe it was."

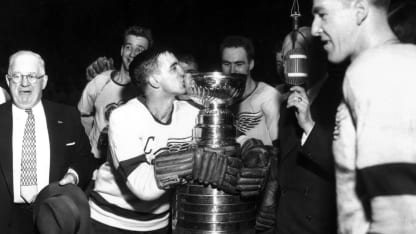

© B Bennett/Getty Images

And so this teenager arrived in the NHL with fire in his belly and an enormous chip on his shoulder, at 19 in his rookie season finishing just out of the League's top five in penalty minutes.

"A 6-foot-2 guy, he can give me a shiner, he can cut me, I can go in and get stitched and come back out," Lindsay said, distilling his philosophy. "He's not going to threaten me, he's not going to scare me. I'll be back and I'll scare him before the game is over."

In the Original Six days, teams played each other 14 times per season, which only made emotions boil that much more.

"You never had to get him that night, that month, even that season," Lindsay said of exacting revenge on an opponent. "If he got you dirty… I never got people dirty [but] I'd get ya.

"I say 'dirty.' Well, I got my elbows into your head and what have you. I never would purposely try to injure anybody. But I'd purposely try to get you out of the game if I could … intimidate you. 'When Lindsay comes on the ice, where is he?' That's the way I wanted him to think. When I came on the ice, 'Where the hell is he?'

"I loved the corners," he continued, eyes sparkling. "That's where you found men. You found more chickens. You knew who the chickens were on the other team because they'd always back off a little bit. If I was coming, they knew they were going to get lumber or elbows or anything. They were going to get into the screen [before there was glass]."

Toronto newspaper writers would nickname him "Terrible Ted" and, later, "Scarface," and he never tried to play to nor disprove the labels.

"I was there to win," he said. "If it meant taking you to the boards or whatever it was, intimidation would be the best way to do it. …

"Everything was fun. I couldn't wait 'til the next game. Some nights I was so good but some nights I was so bad, I couldn't wait 'til the next game to prove I wasn't that bad. It was personal within me, I didn't talk to anybody about it. I knew what my capabilities were. I didn't need a coach to get me up, I was up for everybody."

Famously, Lindsay's bid to form a players union would run him afoul of Red Wings general manager and coach Jack Adams, about whom all these years later he has more than a few sour words.

"Those five consecutive [championships] that Montreal won [from 1956-60]," Lindsay said, color rising to his cheeks. "That jackass Adams, the dumbest manager that ever was in office, he traded away nine players from our Stanley Cup team of the year before. Montreal deserved to win. But if Adams hadn't done that, we'd have won those five - maybe we'd have won three and Montreal two, or vice versa."

Indeed, Adams stripped the mid-'50s Red Wings for parts, trading away the core of a team that had won four Stanley Cup titles in six years. Adams and Lindsay weren't speaking near the end of the player's Red Wings tenure, no matter that Lindsay was the GM's hand-picked captain for his intensity and free spirit.

Adams relieved him of the "C" for no logical reason and then, in one of the NHL's most lopsided, unthinkable trades, the GM shipped Lindsay and goaltender Glenn Hall, another future Hall of Fame member, to Chicago for Forbes Kennedy, Johnny Wilson, Hank Bassen and Bill Preston.

With Chicago, Hall would become the League's pre-eminent goaltender of his day; Lindsay, with less than a full heart, played three seasons of good but not great hockey before retiring to private business.

"I still had Red Wings tattooed here, and here," Lindsay said, tapping his heart, then his backside.

This wasn't the way he wanted to go out. He visited Sid Abel, his former Production Line centerman who by now was Detroit's GM, to explain he wanted to be remembered as a Red Wing, not a Black Hawk.

"Sid said, 'Why don't you come back to play?' " Lindsay recalled. "I laughed at him but Sid said, 'Seriously, I think you can help us.' I'd been retired for four years. I went home and told my wife and she didn't want me to do it. I talked to Marty (Pavelich) and he didn't want me to do it."

He grinned.

"But I loved my game. So I overruled them both and came back."

He signed a one-year contract for the 1964-65 season, a move that many would mock as a publicity stunt. Adoring Red Wings fans blew out the walls of the old Olympia when he returned.

As he recalled their tumultuous welcome, his eyes welled up.

"To get the reception that I got when I came back …" he said. "The years I was here, I produced for the people. I didn't cheat them. That's all. It doesn't mean anything to anybody else, but it means a lot to me."

And then Lindsay dissolved into tears.

In 69 games, he scored 14 goals and added 14 assists, leading the Red Wings to a first-place finish and within one win of a berth in the Stanley Cup Final. Some publicity stunt.

Lindsay retired again, for good, but remained in hockey as a U.S. television color commentator and as Red Wings GM for three-plus years at the end of the 1970s.

Today, he can't go anywhere in Detroit without fans stopping him, even if virtually none of them ever saw him play. Lindsay is hugely involved and absolutely beloved in the community, running his foundation and contributing to many worthy causes.

He is within a few pounds of his playing weight, religiously works out three times a week, and dotes on his wife, Joanne, and a large family that includes great-great-grandchildren. He follows the game that remains his lifeblood, even if he says his nearly 91-year-old body prefers sleep to late nights at the Joe.

His legacy is secure, and Lindsay sums up in a few words how he'd like to be remembered by fans and by the game that he often would take by the scruff of the neck during his wild, fabulous prime.

"I hope it's good, what they would say," he said. "Maybe I didn't always have a good night, but I never cheated them."

Of his reputation that's pure platinum:

"I represent my family, my mom and dad," Lindsay said. "They gave me a proper upbringing and I've tried to follow that all my life. I've kept my nose clean, as much as I could."

And even he chuckled at those words, before adding:

"Away from the ice."