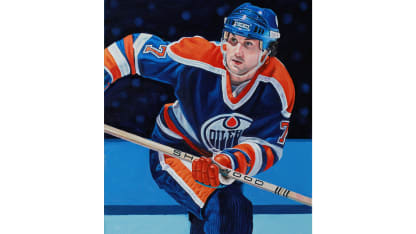

Paul Coffey didn't reinvent the way defensemen play, as

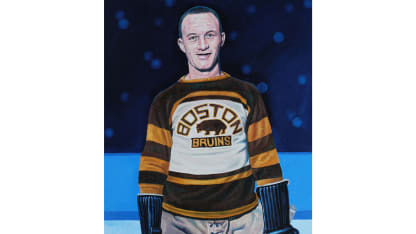

Bobby Orr

did. What Coffey did instead was take the role of offensive defenseman to a whole new level.

Coffey could skate like the wind. One of the great "what ifs" in NHL history would be to have Coffey and Orr, in their prime, square off in the fastest skater competition during All-Star Weekend. But unlike Orr, who popularized the strategy of having a defenseman lead the rush, Coffey would join the play thanks to his great speed. He'd often catch opponents flat-footed and find himself open for an easy goal or a chance to set up a teammate for a wide-open shot.

Of course, it helped that Coffey spent his first seven NHL seasons with the Edmonton Oilers, playing a key role on some of the highest-scoring teams in NHL history. After helping the Oilers win the Stanley Cup for the third time in four seasons in 1987, he was traded to the Pittsburgh Penguins and helped Mario Lemieux become a champion in 1991. Coffey was traded to the Los Angeles Kings on Feb. 19, 1992, and played for six more teams before he retired in 2001 with 1,531 points (396 goals, 1,135 assists). His 48 goals in 1985-86 are still an NHL record for defensemen, and his 138 points that season are one point short of Orr's single-season record.

Coffey was often criticized for focusing on offense at the expense of defense.

But in his NHL100 profile

, author John MacKinnon wrote about Coffey's growth as a player during the 1984 Canada Cup:

"Yes, the knock, particularly early in his career, was that Coffey was suspect on defense, a shortcoming masked in the regular season by the sheer volume of Oilers scoring but potentially problematic in postseason play, when defenses typically tighten up.

"But Coffey famously demonstrated he could dazzle at both ends of the ice with one brilliant shift in a Canada Cup semifinal against the Soviet Union in 1984. The lone Canada player back on a Soviet 2-on-1 in overtime, Coffey slid to his knees and deployed what the coaches call a "good stick" to intercept a pass in his own zone.

"Transitioning to offense in an eyeblink, Coffey moved the puck into the Russian zone where, after some intense sustained pressure, Mike Bossy scored the game-winning goal by deflecting a Coffey slap shot into the net.

"With that performance, Coffey had arrived as a world-class defenseman in the eyes of many observers. In 1985, that sentiment was validated when he won the Norris Trophy as the League's top defenseman for the first of three times. Coffey also won the Norris in 1986 and then again in 1995, with the Detroit Red Wings.