Flyers have had feisty 50 years

Looking back at memorable chapters in Philadelphia's unlikely NHL history

© Len Redkoles/Getty Images

They included the Philadelphia Quakers, who in their lone NHL season, 1930-31, went 4-36-4 in a 44-game season. Their .136 points percentage is the second-lowest in League history.

The last of a series of minor league teams to give the city a shot, the Philadelphia Ramblers of the Eastern Hockey League, had left town in 1964.

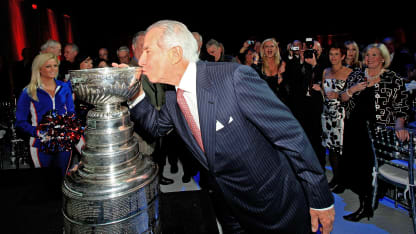

"I was young and full of enthusiasm," Snider, who died April 11, 2016, said in the 1991 documentary "The Philadelphia Flyers -- 25 Years of Pride and Tradition."

© L Redkoles/Getty Images

"I had seen hockey and loved it. I had seen its success in the six cities that had it. But I didn't realize the history of hockey in Philadelphia or in other places. Maybe if I had, I wouldn't have gone through with it."

But he did go through with it, creating a team that has captured the heart and soul of its fans, in good times and bad, one that not only represents the grit of its city but has become a part of its fabric.

The Flyers won the Stanley Cup in 1974 and 1975, the first of the Second Six expansion teams to win a title, and have been to the Cup Final six other times, most recently in 2010. They've made the Stanley Cup Playoffs 38 times in their first 49 seasons, and their 35-game unbeaten streak (25-0-10) in 1979-80 remains the record for the four major North American professional sports.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Since joining the NHL for the 1967-68 season, the Flyers have 1,929 wins, third-most in the League behind the Montreal Canadiens (2,051) and Boston Bruins (2,048); the next-winningest Second Six team is the St. Louis Blues with 1,765.

"It was considered one of the franchises that would not succeed," said Jimmy Watson, a defenseman on the Cup championship teams. "But it has turned out to be one of the best franchises in the entire League."

Countless moments have shaped the first 50 years of the Flyers. Here are four unforgettable chapters in their history:

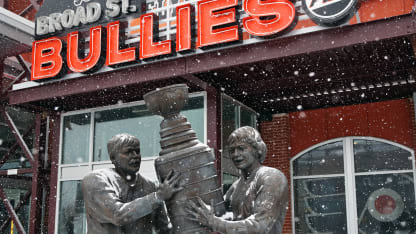

Of Bobby and Bullies

Snider had seen enough. The Flyers had made the playoffs their first two seasons, but had been pushed around each time by the bigger, more physical Blues.

"We played St. Louis and they had the Plager brothers (Barclay and Bob) and Noel] Picard, and these guys were tough fighters," Snider said. "… Teams had in those days what they called a policeman. When John Ferguson [of the Montreal Canadiens] takes on Simon Nolet, Simon Nolet didn't do bad in that fight but he should have gotten the hell beat out of him. He was so scared. But when I see those kinds of things, I think, who said there can only be one policeman? We're not going to be intimidated."

At the 1969 NHL Draft, Snider vowed it never would happen again and made a decision that would define the Flyers.

"I said to [assistant general manager] Keith [Allen], 'I don't ever want to be pushed around again,'" Snider said. "I said, 'We might not be able to skate with these guys, we may not have the talent the Original Six have, but we'll build our team with one thing: We can be as tough as anybody else.'"

With the No. 6 pick, the Flyers selected Bob Currier, a 6-foot-6 center with Cornwall of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League. The selection came over the objection of Flyers western scout Jerry Melnyk, who stormed out of the room.

Snider had a great deal of respect for Melnyk, so he sent Allen to learn what was wrong.

"Keith comes back and says Melnyk said he was shocked because there's this kid,

[Bob Clarke

, [who] plays for Flin Flon (in the Western Canadian Junior Hockey League), that Jerry says could step on the ice and be our best player right now," Snider said.

Snider looked at Clarke's numbers and saw back-to-back seasons of 50 goals, 130 points and 120 penalty minutes. He instructed Allen to make sure general manager Bud Poile selected Clarke if he was available when the Flyers picked next.

When their turn came in the second round, they chose Clarke at No. 17.

The Flyers would never be pushed around again.

© Melchior DiGiacomo/Getty Images

Melnyk was right in his assessment; Clarke showed he was NHL-ready from his first day on the ice; by his fourth season, 1972-73, he was named captain.

"No one worked harder on the ice than Clarke," teammate Gary Dornhoefer said. "He led by example and that's what you want a captain to do."

Clarke was the centerpiece, but he had help. Through the draft, the Flyers added skill with left wing Bill Barber (No. 7, 1972) and defensemen Tom Bladon (No. 23, 1972) and Watson (No. 39, 1972), as well as brawn with forwards Dave Schultz (No. 52, 1969), Bob Kelly (No. 32, 1970), and Don Saleski (No. 64, 1969). Trades brought in forwards Rick MacLeish, "Cowboy" Bill Flett, Ross Lonsberry and Terry Crisp, and defensemen Barry Ashbee and Andre "Moose" Dupont, all of whom became big contributors.

None, though, was bigger than Clarke. In 1973-74 he was fifth in the League with 87 points (35 goals, 52 assists) in 77 games. But more than the numbers was the way he led the Flyers.

"He was phenomenal," Schultz said. "Dedicated to the logo on the front of his jersey. Worked so hard every game, every shift. He was our true leader and he led by example.

"If we were up 6-1 or down 6-1 and someone iced the puck, he'd skate as hard as he could down the ice. Winning or losing, it was the same. He was as hard-working a player as there's ever been in sports. He was just dedicated to the game and to his team. It was great playing with him. He just did it all. He never stopped. I can take a couple shifts off, can't play phenomenal every shift. But he played well very consistently and he made everyone else step it up. He wanted to win so bad. I guess all players do, but some can't get there. To handle the pressure and to play as much as he did, it takes a phenomenal athlete."

Clarke's take-no-prisoners attitude permeated the Flyers, who combined skill with brute strength to create a fearful mixture that stormed through the NHL, dominating teams physically and on the scoreboard.

"In that era, you come into the Spectrum, we think about nothing but winning and we think about nothing but taking advantage of you," Kelly said. "No one was going to come into our house and intimidate us or beat us. And we played even tougher on the road. We thought nothing about bench-clearing brawls. We thrived on all that. The more they wrote about us the worse we were."

Writers who covered the team came up with creative nicknames, but the one that stuck headlined an article in The Philadelphia Bulletin on Jan. 3, 1973: "The Broad Street Bullies."

© Len Redkoles/Getty Images

With Clarke leading the charge, and goaltender

Bernie Parent

winning the Vezina Trophy, the Flyers advanced to the 1974 Stanley Cup Final against the Bruins.

The biggest shot of confidence for the Flyers came in Game 2 when Clarke scored in overtime in Boston. The Flyers hadn't won there since their first game in Boston, on Nov. 12, 1967; they had 16 losses and two ties in 18 regular-season and playoff games.

"I scored in overtime and it became a big goal, but at the time it was only winning one game," Clarke said. "If we lose the series it's no big deal."

The Flyers did win the series, defeating the Bruins 1-0 in Game 6 on MacLeish's first-period power-play goal and a 30-save performance by Parent. The game also is remembered for coach Fred Shero's pregame message to his players: "Win together today, and we will walk together forever."

"No truer words were ever said," Kelly said.

There also was Kate Smith famously singing "God Bless America." Video of her performing at the Spectrum still is played before Stanley Cup Playoff games.

Watch: Kate Smith singing 'God Bless America' on Youtube

And the game ended with Hall of Fame broadcaster Gene Hart exclaiming, "The Flyers win the Stanley Cup! The Flyers win the Stanley Cup! The Flyers have won the Stanley Cup!"

Clarke was even better in 1974-75, finishing sixth in the League with 116 points (27 goals, 89 assists) in 80 games and winning the Hart Trophy for the second time; the first was in 1972-73.

The Flyers reached the 1975 Cup Final against the Buffalo Sabres, and again Clarke was involved one of the biggest moments. With the Flyers leading the series 3-2 and Game 6 at Memorial Auditorium in Buffalo scoreless early in the third period, Clarke helped Kelly win a puck battle behind the Sabres' net. Kelly skated in front and scored, and the Flyers went on to win 2-0 and repeat as champions.

Clarke helped the Flyers reach the Cup Final again in 1976 and won the Hart Trophy for a third time. He also won the Selke Trophy in 1983 as the League's best defensive forward; he and fellow Hockey Hall of Famer Sergei Fedorov are the only players to win those two awards.

Clarke retired in 1984, was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1987 and was named one of the 100 Greatest NHL Players presented by Molson Canadian in 2017. Though Clarke is the Flyers' all-time leader in points (1,210), assists (852) and games played (1,144), he remains humble about his accomplishments.

"I guess I'm not real comfortable having the attention directed at me," he said. "Even though I know I played on a great team, was a decent player, and a lot of attention has come my way, I never enjoyed going out of my way to get more attention."

Clarke also had successful tenures as Flyers GM, from 1984-90 and from 1994 until his retirement in October 2006. The Flyers went to the Stanley Cup Final three times (1985, 1987, 1997) and reached the playoffs 16 times in 17 full seasons under Clarke. He is a senior vice president and remains the most important figure in Flyers history.

"He's revered, he's a godlike figure," said Rod Brind'Amour, a Flyers forward from 1991-2000.

'Iron Mike'

The Flyers of the early 1980s were a mix of veterans from the Stanley Cup championship teams plus a few promising young players. The combination, under coach Pat Quinn, worked well enough that the 1979-80 Flyers had the 35-game unbeaten streak and reached the Stanley Cup Final, where they lost to the New York Islanders.

That group didn't have longevity, and Flyers president Jay Snider, who had been named to that position by his father, Ed, in 1983, was looking to make changes entering the 1984-85 season. Bob McCammon was fired as coach and GM; to fill the latter role, Jay Snider hired Clarke, who had just finished his 15th season as a player. Clarke said he wasn't sure if it was the best idea, but that his loyalty to the organization led him to take the position.

"Had I kept playing, which I could have done, I don't know, maybe I would have stayed in hockey," said Clarke, who was 34. "Scouting, coaching. I had no vision of what I was going to do. Jay Snider offered me this position, and I knew I could play for a few more years, but I knew the end was coming. If that's what the Flyers thought was right for me, then OK."

Clarke's first decision was to hire a coach. He settled on Mike Keenan, who arrived having won championships in the American Hockey League, Canadian Hockey League and Canadian university hockey. He also had a reputation for having a tongue as sharp as a skate blade.

"Everybody I talked to said that his style would cause some problems with players, but that he had always won," Clarke said in the Flyers history book "Full Spectrum."

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Keenan installed a demanding style from the first day of training camp in 1984 and never let up.

"He was willing to do whatever it took to get the best out of someone," said Dave Poulin, a forward who was in his first season as captain. "It's a difficult proposition because there are times you don't want to do what's necessary as a coach. I think the best coaches in many respects have to be unreasonable about what a player goes through. The demands on a player have to be so extreme, and it's very hard to get to that point. That's not a reasonable demand, and Mike was able to make unreasonable demands."

Forward Rick Tocchet, a rookie in 1984-85, said he likely would not have played 18 NHL seasons were it not for Keenan.

"I can honestly say that now," Tocchet said. "He got another level out of me. I wasn't the most talented player, but he was the biggest reason I played in the NHL."

Keenan said he never tried to be harsh or hurtful; it was about teaching a young group how to win.

"I tried to bring out more than they thought they could give," he said. "Maybe I was considered to be very firm or very hard on them, but I knew they had potential. The group … I thought they needed to understand they could give more than what was expected or what they expected from themselves."

The 1984-85 Flyers were young (they had the second-lowest average age in the League on opening night, according to the Elias Sports Bureau), but Keenan guided them to the Presidents' Trophy and then to the Stanley Cup Final, where they lost in five games to the Edmonton Oilers.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Though Keenan's fire burned more than a few players, they saw a different side of him the following season.

The Flyers defeated the Boston Bruins on Nov. 9, 1985, for their 10th straight victory, and with five days before they'd play again, Keenan told his players to take the next two days off.

A number of players met up for dinner and drinks after the game that night, among them goaltender Pelle Lindbergh. While driving home early the next morning, he lost control of his car and crashed into concrete wall outside an elementary school in Somerdale, New Jersey. Lindbergh was declared brain-dead; he was removed from life support and died Nov. 11 at age 26.

Stunned teammates gathered at the hospital after the accident.

"It's something you can't believe is happening," forward Dave Brown said. "We were poised to go to the Final again that year and he was the guy that was going to lead us there. There's no plan on how to get through things like that. Something like that happens, you lose your No. 1 goalie, and most of all a friend. It sends the whole team into turmoil. What do you do? He was dead. You just try to cope with it after that."

It was left to Keenan to pick up the pieces of a shattered team.

"Mike did an excellent job," defenseman Mark Howe said. "He got the guys together at his house a couple times. If anybody watched Mike in practice [before that], if the team made a bad pass or two bad passes, the whistle blew and you paid because you weren't focused. We were practicing a few days later and we were as bad as a team can be, and Mike was patient with everybody. He kept everybody together."

"After the tragedy Mike had everyone at his house and it was almost like a three-day cleansing, getting the emotions out of us," Tocchet said. "It was a tough period. We saw a different side of him. We didn't see the tough, it's-all-hockey-hockey [side]. There was another side we saw of him. … It kind of humanized him, absolutely."

Keenan said he drew on tragedy in his own life to help him and the players get through their grief.

"I think that I was more compassionate and sensitive then they thought I could be," he said. "I had some personal experiences. I had lost my [younger] brother when we were young and I had gone through many real late miscarriages. Several. So I dealt with a little bit of mourning before that. It was instinctive … showing them two different sides of my personality, the hard coach and the sensitive human being."

Keenan guided the Flyers to first place in the Patrick Division, but they lost to the New York Rangers in the first round of the playoffs.

A mentally tougher team arrived for 1986-87.

"The core of the group was the same, but it was two different teams," Poulin said. "That team went through so much with the death of Pelle that it was a more mature team in 1986-87."

Among the newcomers was rookie goaltender Ron Hextall, who brought an intensity that spread throughout the Flyers.

"Every time he stepped on the ice he was full-out," defenseman Kjell Samuelsson said. "Even in practice, if you shot high on him he'd get irritated. He tried to stop every puck coming at him."

The Flyers reached the 1987 Stanley Cup Final against the Oilers, who took a 3-1 series lead into Game 5 in Edmonton. Keenan tried every motivational trick he could think of, including some Stanley Cup thievery.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

"Somehow I found the Cup, I don't know how or where, in the building," he said. "I had the trainers dress up a table in the middle of the room and I brought the Cup in and sat it on the table and at that point nobody on that team had ever won the Cup. I said, 'You can look at it but you can't touch it because none of you have earned it. But that's what the prize is, that's what you're playing for.'

"I think there was a little bit of a panic for a while because even the authorities in the NHL couldn't find the trophy."

The Flyers won that night and again in Game 6, on J.J. Daigneault's third-period goal, to force Game 7. But that's where things ended for Philadelphia in a 3-1 loss.

Hextall won the Conn Smythe Trophy y as playoff MVP. In 26 games, he had a .908 save percentage and two shutouts, including a .902 save percentage in the Cup Final.

"That was the best goaltending I've ever seen," Howe said. "He was incredible his first year. For the most part, especially in the Final, as good as we played and as close as we came, it wouldn't have been that close without Ron Hextall, there's no doubt about it."

After the Flyers lost to the Washington Capitals in the first round in 1988, Clarke grew tired of listening to players complain about Keenan and fired the coach.

"Mike was so cruel to some of the players that I had a couple players come in on their own crying," he said. "Sit in front of me and cry, said 'Let me go home, I hate Keenan so bad, he's just so cruel to me.'"

Keenan went on to coach seven other NHL teams, winning the Stanley Cup with the New York Rangers in 1994, and will coach Chinese team Kunlun Red Star in the Kontinental Hockey League next season. He said his four seasons in Philadelphia gave him the confidence he needed.

"I think having that experience, molding a group of players that was the youngest group of players in pro sports [in 1984-85] and having success, you take a level of confidence out of it that you can build a team or help build a franchise," Keenan said.

'The Big E' arrives

Eric Lindros

was going to play somewhere in the NHL and the Flyers were determined to have it be in Philadelphia.

Lindros, considered by many the heir apparent to Wayne Gretzky and Mario Lemieux, had been selected by the Quebec Nordiques with the No. 1 pick of the 1991 NHL Draft but refused to play for them.

The Nordiques demanded a high price for the center, but the Flyers felt they were one of the few teams that could meet it.

"We thought there was maybe three or four teams that were even in the running," said Russ Farwell, the Flyers' general manager at the time. "We just didn't feel there was very many teams that would have both the motivation and the assets to do that trade."

On June 20, 1992, the Flyers agreed to trade Hextall, defensemen Steve Duchene and Kerry Huffman, center Mike Ricci, forward prospects Peter Forsberg and Chris Simon, first-round draft picks in 1993 and 1994 and $15 million to the Nordiques for Lindros.

Hours later, though, they were informed the Nordiques had traded Lindros to the New York Rangers.

The Flyers filed a grievance, and after a weeklong hearing an arbitrator ruled their trade with the Nordiques was valid and awarded his rights to Philadelphia.

"We erupted when [the arbitrator awarded Lindros to the Flyers]," Jay Snider said of the decision, announced June 30. "We had [the phone] on mute. I had no idea that the entire staff was outside my office door listening. When they heard us cheer, then I heard the whole office cheer."

Lindros (6-foot-4, 240 pounds) quickly became a dominating presence, scoring 41 goals as a rookie in 1992-93 and 44 goals the following season.

"He changed the game," Gretzky said. "When Eric came in, he was that new physical power forward that happened to have really good hands."

© Denis Brodeur/Getty Images

He didn't just change things on the ice. The Flyers became more popular outside Philadelphia (Farwell said Lindros' jersey at one point was the second-best seller in the League, behind Mario Lemieux's), and the Flyers also had a big name to help them secure financing for a new arena. (They moved from the Spectrum to the CoreStates Center, now Wells Fargo Center, prior to the 1996-97 season.)

Things changed for Lindros and the Flyers in 1994-95 when forward John LeClair was acquired in a trade with the Montreal Canadiens in February. Coach Terry Murray put Lindros between LeClair (6-3, 233) and Mikael Renberg (6-2, 235). They formed the "Legion of Doom" line and wreaked havoc on the NHL.

"It was really impressive how they could take over a whole game and put a team on its heels," said Jim Montgomery, the then-Flyers forward who is credited with giving the line its nickname. "It was so rare to see a line with that speed and size."

"We played similar styles," Lindros said. "We enjoyed coming to practice. We had a lot of fun at practice together, and I think that really paid off in terms of what happened on the ice during games. I think there was a direct correlation to that. You've got a group of guys that truly enjoy coming in in the morning and being around each other all the time, you're going to have much better success."

LeClair scored 50 goals three straight seasons playing alongside Lindros and credits him for his NHL success.

"When I came to the Flyers I got the confidence in me as a player," he said. "Playing with Eric and Mikael, I had some success and built that confidence."

In 1994-95, Lindros led the NHL with 70 points (29 goals, 41 assists), won the Hart Trophy and helped the Flyers reach the Eastern Conference Final after five seasons out of the playoffs. In 1995-96 Lindros had NHL career highs in goals (47), assists (68) and points (115).

Lindros led the Flyers past Lemieux and the Penguins the first round in 1997, sending Lemieux into his first retirement. After Philadelphia eliminated the Buffalo Sabres in five games, Lindros scored three goals against the Rangers in a pivotal Game 3 win in the Eastern Conference Final. The Flyers won the series in five.

It was one of the last good moments for Lindros during his time with the Flyers. During the Cup Final against the Detroit Red Wings, he had one goal and the Flyers were swept in four games.

© Robert Laberge

Lindros sustained the first diagnosed concussion of his NHL career on March 7, 1998. It began a career-changing spiral.

He sustained his third concussion of the 1999-2000 season on March 5. Lindros played four more games but was removed from the lineup prior to a game March 13, and missed the rest of the regular season. He publicly criticized the Flyers' training and medical staff on March 23, and Clarke responded four days later by stripping Lindros of the captaincy he'd held since 1994-95.

Despite sustaining another concussion as the result of an on-ice collision with a teammate during a workout, Lindros returned to the Flyers for Game 6 of the 2000 Eastern Conference Final against the New Jersey Devils. He scored a goal, but the Flyers lost 2-1 and the series was even at 3-3.

The Flyers hoped Lindros' strong play would carry over into Game 7, but those hopes were dashed with 12:10 left in the first period when a hit by Devils captain Scott Stevens knocked out Lindros with another concussion. The deflated Flyers lost.

"It was devastating," LeClair said. "That was a violent hit. The way he fell, he was out cold. It was scary."

Lindros never played another game with the Flyers. He sat out the 2000-01 season to recover from his injuries and wait for a trade. It finally came Aug. 20, 2001, when he was traded to the Rangers for defenseman Kim Johnsson, forwards Jan Hlavac and Pavel Brendl and a third-round pick in 2003.

In eight seasons with the Flyers, Lindros had 659 points (290 goals, 369 assists) in 486 games. His 1.36 points per game between 1992-93 and 1999-2000 ranked third among players with at least 200 games, behind Lemieux (2.11) and

Jaromir Jagr

(1.45).

Lindros was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2016. There to greet him was Forsberg, who had been inducted in 2014. While Forsberg dealt with his own injuries, he played 16 seasons (including parts of two with the Flyers from 2005-07) and helped the Colorado Avalanche win the Stanley Cup in 1996 and 2001, winning the Hart Trophy in 2003.

Lindros remained estranged from the Flyers until he was invited to play in the 2012 Bridgestone Winter Classic Alumni Game. He and LeClair were inducted into the Flyers Hall of Fame in 2014, and he has been a frequent presence around the Flyers during their 50th anniversary season.

"Much of what occurred was so long ago," Lindros said when he was inducted into the Flyers Hall of Fame. "We're looking at 14, almost 15 years now. It was a real honor to be invited back [to the alumni game]."

The comeback

The Flyers rallied from adversity so many times during the 2009-10 season that it almost felt like a natural state for them.

"It's kind of where our season has been," defenseman Matt Carle said the morning of Game 6 of the 2010 Stanley Cup Final against the Chicago Blackhawks. "We've been faced with some tough times. If we're going to win this series, this is how we'd do it."

Hours later, not even the resilient Flyers could get up from the punch Patrick Kane and the Blackhawks hit them with when Kane scored the Cup-winning goal in overtime.

The fact that the Flyers had gotten that far was nothing short of amazing, considering where they started. A dysfunctional roster led to a rough start, the firing of coach John Stevens, who was replaced by Peter Laviolette, and the Flyers' plummeting to 29th in the League standings after a 4-1 loss to the Florida Panthers on Dec. 21.

"There was a lot of questioning going around," forward Daniel Briere said. "It was a tough time to be around the dressing room. We weren't having a lot of fun. But at the same time, looking at our team, there's always that, not confidence, but you just knew that things could turn around."

They did, and the Flyers went into the final weekend of the regular season needing two points from a home-and-home set with the New York Rangers to make the playoffs. They lost the first game 4-3 at Madison Square Garden on April 9, leaving a one-game, winner-take-all rematch in Philadelphia on Sunday, April 11.

After practice on the day between games, Laviolette gathered his top offensive players for a bit of extra work.

"[Mike] Richards, [Simon] Gagne, Claude Giroux, [Jeff] Carter and myself watched video of Rangers goalie Henrik Lundqvist on breakaways," Briere said. "And after Saturday's practice he made the five of us practice our shootout moves at the end of the workout."

The work paid off when the finale went to a shootout. Giroux scored in the second round to give the Flyers the lead, leaving goaltender Brian Boucher to make one final save, on Olli Jokinen. The Flyers won 2-1 to make the playoffs.

"I was almost sick," forward Scott Hartnell said. "It was just incredible. I literally was almost sick."

"It's like we could be done right away if he [Jokinen] scores," Gagne said. "You're just like, you can't believe it's April 11 and this might be the end of your season."

Jokinen came straight up the middle of the ice, cut to the right and then stepped back toward to middle to try to deke Boucher's pads open. But the goalie stayed up and easily stopped a backhand attempt, igniting the crowd and sending Boucher into a fist-pumping, one-legged victory jig as teammates spilled onto the ice.

"You're taught as a hockey player not to get like that, especially the goaltender," he said. "You have to play the next night, you have the next game ahead of you. You don't celebrate the victories as much as you might think. You have to get ready for the next shot, the next game. But the enormity of the situation, I think it was called for to have that type of celebration, especially at home."

© Brian Babineau/Getty Images

They defeated the New Jersey Devils in the first round in five games but during the series lost Carter, Gagne and forward Ian Laperriere to injuries. The situation got worse when they lost the first three games of their second-round series against the Bruins.

Only two NHL teams had trailed 3-0 in a series and come back to advance, but that didn't seem to faze the Flyers.

"The year was a roller coaster and up and down," Richards said. "A lot of things happened [but] we didn't get discouraged by anything. … I think going through that earlier in the year kind of helped us, especially in the Boston series. You know, losing a couple games in a row and bouncing right back, so it's always good to go through some adversity and come through it together."

Gagne scored in overtime in Game 4, and then the Flyers were leading 1-0 in Game 5 when Boucher injured both knees during a pileup in front of the net. Michael Leighton, who was in uniform for the first time since spraining his ankle against the Nashville Predators two months earlier, entered the game and made 14 saves to finish the 4-0 shutout.

The Flyers won 2-1 in Game 6 to send the series back to TD Garden in Boston. The Bruins took a 3-0 lead 14:10 into the first period of Game 7 when Laviolette used his timeout to settle his players.

"The message was, 'Just score one goal,'" he said. "Get on the board, get in the game. That first goal, for me, was huge."

James van Riemsdyk scored 3:02 later, and Hartnell and Briere scored in the second period to tie it. At 12:52 of the third, Gagne scored to give the Flyers a 4-3 lead they wouldn't relinquish.

"There's things in your life you're always going to remember, and that's one thing that was amazing the way it happened," Leighton said. "Being down 3-0 [in the series] and being down 3-0 in Game 7, it's just almost like it was meant to be the way it happened."

The Flyers' improbable trip to the Final saw them get knocked down again when they lost the first two games in Chicago. But defenseman Chris Pronger put the focus on himself rather than Philadelphia's struggles by stealing the game pucks after the first two games.

"I'm sure there's a method," Briere said. "He seems to be disturbing a lot of people. We're a team that disturbs a lot of people. I guess he fits right in."

The Flyers rallied to tie the series with wins in Games 3 and 4 in Philadelphia. In Game 5 at Chicago, the Blackhawks took a 3-0 first-period lead and won 7-4.

The Flyers fell behind 1-0 late in the first period of Game 6, but Hartnell scored with 26.5 seconds left to tie it. They were down 3-2 when Hartnell again tied the game with 3:59 left in the third period.

Philadelphia was woozy but nearly landed a crushing blow 20 seconds into overtime when Richards threw a bouncing puck in front to Giroux, who couldn't get much on the shot, and Blackhawks goalie Antti Niemi was able to stop it.

"We had the feeling we were going to win the game and go win Game 7," Gagne said. "That's the way we believed this year. We felt it was made for us to make history. We thought it was going to happen right to the end."

But the end for the Flyers came when Kane got the puck on the left side of the Flyers zone, beat defenseman Kimmo Timonen and slid a shot under Leighton's pads at 4:06 of overtime.

The Flyers were left to watch as the Blackhawks celebrated. They had lost, but they were far from losers.

"I'm very proud," Pronger said that night of his teammates. "The way we battled to come back time and time again. There was no quit in this team, even tonight."

The comeback was just another example of the determination that has endeared the Flyers to their fans during the past 50 years.

"We always liked to play the game hard," said Brown, who has spent 24 of his 35 seasons in professional hockey as a player, assistant coach or scout for the Flyers. "Philadelphia fans want a blue-collar guy who goes out and works hard every day and brings some toughness."

© Len Redkoles/Getty Images