As the 1971 Stanley Cup Playoffs approached, no team in hockey was more feared than the Boston Bruins. They had the greatest player in the sport, Bobby Orr. They had the most prolific offensive force in the game, Phil Esposito, who had just scored 76 goals in the regular season. The defending Stanley Cup champions had rung up numbers as if they were playing pinball, averaging 5.1 goals per game and counting four players with more than 100 points, led by Esposito (152) and Orr (139).

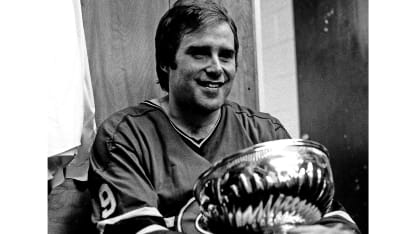

Paired against the Montreal Canadiens in the opening round, the Bruins seemed to have little cause for concern, having won five of the six meetings during the season, including two blowout victories -- by a combined score of 13-5 -- soon before the playoffs. When Al MacNeil, the Canadiens coach, announced that he was going with a 23-year-old kid out of Cornell University, Ken Dryden, as his goaltender, more than a few observers figured the Bruins would pummel Dryden, a veteran of six NHL games.