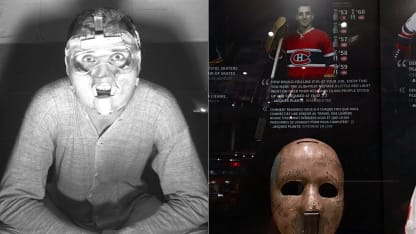

It took the primitive mold a half-hour to harden on McKinney's face, then 60 excruciating minutes to pull it off, a release agent like petroleum jelly not having been first applied. Bill Burchmore, the Fibreglas Canada Ltd. sales and promotion manager who had ladled on the compound, would use the form to make the mask Montreal Canadiens legend Jacques Plante would famously wear in a game on Nov. 1, 1959, forever changing the face of NHL goaltending.

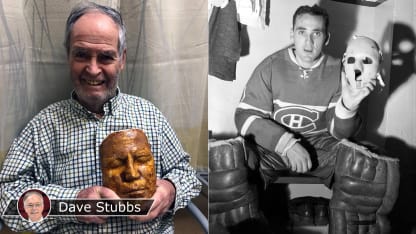

Two months ago, McKinney, now 87, gave the mold to his son, Scott, who with his father's encouragement travelled from British Columbia to Toronto to present it on Feb. 22 to Phil Pritchard, curator of the Hockey Hall of Fame, and Craig Campbell, manager of the shrine's resource center and archives. The mold will be showcased at the Hall in a display charting mask evolution, one that's rich with Plante items.

There will be much more heard about Plante in the days ahead with Carey Price now two wins from passing the late legend's record of 314 regular-season victories with the Montreal Canadiens.

Scott McKinney (center) presents Craig Campbell (left) and Phil Pritchard with the 1959 mold of his father's face.

Plante had been toying with a mask in practice through the 1950s, cutting a broad eye-hole in a plastic shield made by Delbert Louch of St. Mary's, Ontario. Hailed as "the shatterproof face protector for all sports," the Louch shield never caught on, leaving the forehead exposed and fogging up in frosty arenas.

Burchmore was at the Montreal Forum for a Stanley Cup Playoff game in April 1958 when a barefaced Plante was drilled in the forehead by a puck. In the NHL's one-goalie days, the game was delayed 45 minutes while Plante left for repairs.

Returning to his office the next day, Burchmore gazed at the fiberglass mannequin on his desk. He wrote to Plante to tell the goalie he could make him a space-aged mask -- and this almost before the space age.

Plante's initial indifference did nothing to dampen Burchmore's enthusiasm. And it's here that McKinney, then an eager sales trainee with Fiberglas Canada, entered the picture.