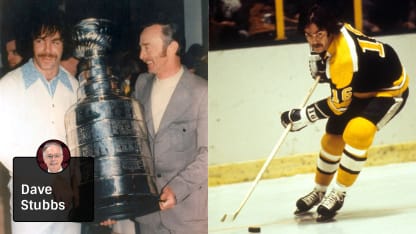

Sanderson would give not one championship ring to his father, but both of them.

"I didn't wear them in public. The 1970 ring was like a university class ring, not like today's monstrosities, but the diamond in the middle would still rip my pants pocket and all the change would run down my leg onto the ground," he said, laughing.

Years later, when Sanderson brought his fiancée, Nancy, to meet her future in-laws, Sanderson asked his father to see the rings.

"So he walked across the living room with a little knife that he carried all the time and cut the rings out of the hem of the curtains," he said. "I couldn't believe it, but that's where he kept them, so they wouldn't be stolen. He wouldn't wear them because he said that only the Cup winner had that right."

Harold Sanderson returned the rings that night to his son, who in time gave them to his own sons with Nancy: Michael, now 26, and Ryan, 24.

"They don't wear them, either," Sanderson said. "They could, but they don't."

Father's Day is something different yet very special now to Sanderson, who cherishes memories of his dad as he enjoys his own two sons.

"My father was so darned good, so thoughtful," Sanderson said. "He was there for me all the time. I tried to make sure my boys had what they wanted, what they needed, and maybe a little extra if I could get it."

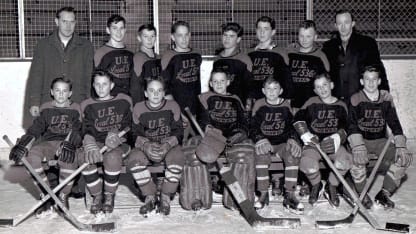

Michael and Ryan Sanderson played many sports growing up, their father unable to participate because he had his hips operated on 10 times, finally surgically replaced. When he yearned to join their games, Sanderson's mother, who died in 2012, had some good advice of her own.

"Mom told me, 'They don't need you to play, they just need you,' " Sanderson said. "And I think back to what (New York Yankees slugger) Mickey Mantle once said: 'If I knew I'd have lived this long, I'd have taken better care of myself.' "

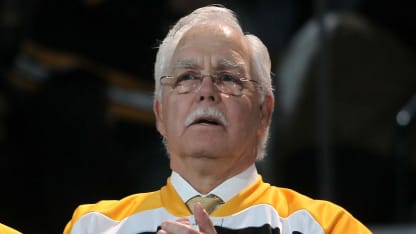

On this Father's Day, Sanderson will think of his father, Harold, whose guidance and friendship remain larger than life.

"Dad was the greatest man I ever knew," he said. "He was the only hero I've had in my life."