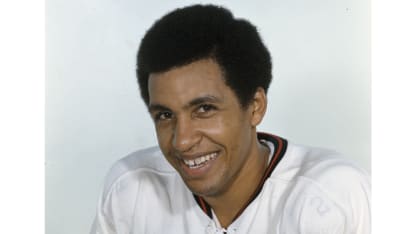

Editor's note: As part of the NHL celebrating Black History Month throughout February, NHL.com will present first-person essays by some of the game's key Black players and executives. Today, Alton White, the second Black player to play professional major league ice hockey, tells his story of overcoming racial taunts to become a role model on and off the ice.

Black History Month essay: Alton White

Second Black player in professional major league hockey on overcoming racial taunts, being role model

By

Alton White / Special to NHL.com

In 1972 when I played my first game for the New York Raiders of the World Hockey Association, I wasn't aware at the time that I was only the second Black player to play in a major professional hockey league. After so many years in the minors, I was more focused on the chance to play professionally in a new league than making history. It was a long journey to this moment.

I was born in Nova Scotia. My family moved to Winnipeg when I was only 8. We grew up among an influx of Ukrainian immigrants but were the rare Black family in our town. There was an eight-year age difference between my next-to-youngest sibling, so I was the only Black child in my grade school and then high school.

Despite all this, I was fortunate not to experience racism in the extreme as would be the case when I started my hockey career in the United States. This is not to say that discrimination didn't exist in Canada, but I didn't experience it.

I learned to skate on a natural sheet of ice at 3 years old. When I started playing hockey, skating was my biggest asset, despite not being the biggest player on the ice.

At the age of 10, everything changed when former NHL goaltender James "Sugar Jim" Henry took notice of me. Henry was working as a scout and on a local radio show said that he saw me play and remarked: "if that little kid grows and keeps developing, he should be playing in the NHL one day."

When I heard that, I believed it was possible for me to play in the NHL. This was 1955 and I didn't know of any Black players in the NHL. Then in 1958 when I was at a local community center where I played, there was an older guy we knew who said I won't be the first. I could not figure out what he was talking about. But then I later found out that Willie O'Ree made history with Boston in January of that year.

As a teenager, I signed with the New York Rangers. This was before the NHL Draft as we know it. At the age of 20, they sent me to Fort Wayne, Indiana for my first year of minor pro. That was the first time I'd ever run into racial discrimination. Imagine, this was the first time I was away from home and made painfully aware that I am Black. With three of my Canadian teammates who also joined the team that season, we went looking for a place to rent. There was a house that seemed okay for us but the woman renting it pulled one of the other players aside and said. "you can't live here because he's colored."

You read about these things in school about Jim Crow and racism in America. I never really thought I'd be in that situation. But here I was. It set me back.

Things got worse. When we went on road trips. The names I heard were awful. Every possible racial slur, I heard it, including the N-word. I had to develop thick skin because you couldn't do anything about what was said in the crowd. Maybe they were trying to get me off my game. I don't know. That first season was tough, and I am surprised I made it.

The next year, I moved on to the Columbus Checkers where I played three seasons. In Columbus, I was fortunate to meet Ann Walker, an African American journalist at WVKO-AM radio. She came to a couple of games and I got to know her and her family and spent a lot of time with them. It felt like home being around them. My experience in Columbus was the best of my early hockey experience as a professional. On the ice, I got better every year. In my last year in Columbus, I was named Most Valuable Player.

By the end of the 1971-72 season, I felt I'd waited my turn. My team, the Providence Reds, owned my contract so if an NHL team was interested in me, they would have to buy it outright before signing me. Providence had an arrangement with the NHL's California Golden Seals at the time and there were players who would move up to the big show. I saw other players come and then go to Oakland but there I was still in Providence.

In 1972, the World Hockey Association's New York Raiders drafted me and that is when I became the second Black player in major professional hockey. I wasn't particularly happy in New York. I'm more of a small-town player who prefers keeping a low profile. That and not playing regularly. I asked for a trade and it was granted, sending me to the Los Angeles Sharks, where I finally got a chance to play. That season I scored 21 goals and finally felt like all those years of hard work and perseverance paid off.

That first season marked not only being the second Black player in a major professional league but the first to ever score a hat trick. I would do that twice in the season.

We played the Chicago Cougars on Jan. 10, 1973 when I got my first hat trick. I scored all three goals during a seven-minute stretch.

The second hat trick came in Minnesota with Jack McCartan (the hero of the United States gold medal team at the 1960 Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley) in net. After I did, someone threw a banana on the ice. Can you imagine being focused on the game, concentrating on what you are doing and getting the chance to score and then someone throws a banana on the ice.

Throughout my career, my teammates were supportive whenever something happened. But more than anything, I wanted to be recognized for my hockey ability than the taunts I faced during a game.

Still, I was pretty fortunate. Very few people get to play professional hockey. Even with the difficulties on the ice, I met some wonderful people in each of the cities I played and stay in touch with so many people from those days.

As athletes, we have a responsibility as role models. I felt that, especially as a Black player. Whenever I saw Black fans at the game, I would try to catch their eye and acknowledge them.

One of my favorite stories occurred at one game when I was with Los Angeles. There was a young boy who caught my eye. He shouted my name and I looked over and gave him a wink. He was so moved by the gesture that he said it changed his life and helped him to think about things differently and opened up the possibilities of the world.

That young boy would become an influential member in Washington state politics. Eric Pettigrew was a member of the Washington House of Representatives for almost twenty years. Now he is the Vice President of Government Relations and Outreach with the NHL's newest club, the Seattle Kraken.

Eric and I are now good friends who talk quite often. These are the moments in hockey that mean so much to me.

It's great to see so many changes in who participates in hockey these days, especially at the youth level. There are so many more Black children playing hockey but also children of Asian and South Asian descent. There are lots of kids of color that are playing. If they get a chance to participate you know they can excel, not just in sport but largely in life.

When you get an opportunity, you have the chance to excel. Even if many who develop along the amateur side don't turn pro, a lot of them are going through the universities in the States. Kids are getting a chance to play, and they get an education.

Now as I'm 75 years old, I am gratified for my time playing the game. I'm fortunate that after all this time people have not forgotten me. I get cards from all over Canada and the United States and requests for signed pictures. There are even some from Europe! Most of these correspondences are from kids who want to know how I'm doing and wishing me well and asking me hockey questions. It is really gratifying to know that they haven't forgotten because for a long time I was unheard of.

Now I know a little of what Willie feels. He's done so much for the game and is a great ambassador for the sport. I'd like to think that all of us Black players who played contributed to the game in our own way.