As part of the NHL's Centennial Celebration, longtime hockey reporter and analyst Stan Fischler, "The Hockey Maven," will write a biweekly scrapbook for NHL.com. The scrapbook will look at some of the strange-but-true moments from the NHL's first 100 years.

Albert Suomi, Butch Schaefer, Bun LaPrairie, Curly Brink, Ike Klingbeil. While these names hardly ring a bell among contemporary hockey buffs, for a brief spell during the 1936-37 and 1937-38 seasons they formed the core of one of the noblest, if not most successful, NHL experiments.

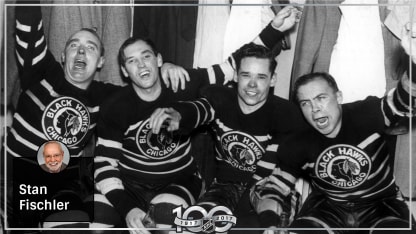

All-American Black Hawks

Chicago used United States-born players to win unlikely Stanley Cup in 1938

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

Major Frederic McLaughlin, the eccentric president of the Chicago Black Hawks, had long dreamed of the day when he could ice an entire team of United States-born hockey players rather than the Canada imports used by every NHL team in the 1930s.

Needless to say his scheme, like so many of his ideas, was the laughing stock of his colleagues on the NHL Board of Governors. Everybody knew at the time that there were only a handful of competent American skaters and they belonged in the minors, not the NHL. However, the Major was not to be denied.

At the start of the 1935-36 season he planted the seeds of his grand plan. McLaughlin had heard enthusiastic reports about a young goalkeeper from Eveleth, Minnesota, named Mike Karakas. He designated the ruddy-faced Karakas as his starting goalie and traded veteran Lorne Chabot to the Montreal Maroons. This was only the beginning.

The Major knew his All-American plan had leaked to some of his players and they already were resisting it in principle, if not in fact. "We thought it was pretty ridiculous," said Johnny Gottselig, one of the better Chicago forwards.

With that in mind, McLaughlin realized he had to administer his program with a touch of subtlety. He quietly ordered his scouts to scour the northern sector of the United States for top stickhandlers, and they returned with the names of Suomi, Brink, LaPrairie, Schaefer, and Klingbeil, among others.

Armed with the list, McLaughlin ordered the Americans to Chicago but took pains to have them arrive more in the manner of espionage agents than hockey players involved in one of the most daring schemes in the game's history.

The Major was, however, afraid that the grand plan might collapse before it got underway. He wanted it to be done right. And what better way to insure this than to order the Americans to undergo workouts at a secret location?

Chicago Arena was picked as the site for the Americans to conduct their scrimmages. Now that the recruits were in town and supposedly honing themselves to sharpness, the Major became more and more confident. Until he finally decided it was time to break the news to his Black Hawk veterans, the Canadians.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

The veterans betrayed utter contempt for the newcomers. They pretended they didn't exist, ignoring them at every turn when they met in the dressing room. Once on the ice it was even worse. The Americans skated against the Canadian-born Black Hawks and blood gushed from the newcomers. "It was tough," Klingbeil said. "You name it, high sticks, trips, they threw it at us."

But McLaughlin was not about to be pushed around by his players. He was determined to integrate the Americans into the lineup and did just that. Rather than icing an all-Canadian line and an all-American line, he insisted that a Canadian forward line skate with defensemen Schaefer and Klingbeil.

Soon the players got to know each other and the bitterness gradually began to subside. More importantly, the Canadians realized that these American kids weren't so bad after all. They held their own in regular games against NHL opposition and the Black Hawks actually won a few games here and there.

McLaughlin remained cautious about tossing all five U.S.-born skaters onto the ice at once, but when the Black Hawks sagged and appeared destined to finish out of the Stanley Cup Playoffs he decided to give it a try. So with only one home game remaining, against the Boston Bruins, McLaughlin announced that his five-man all-American unit would work in that game.

One might have expected the Major's announcement to be greeted with lukewarm approval from his fellow owners, at the very least. After all, the Black Hawks were out of the race and any means to draw fans might have been considered justified by League bosses.

Instead, news of the all-American plan inspired a torrent of abuse from Montreal to Toronto to Boston. Because each of the club managers was Canadian-born, they interpreted the idea as an insult to the integrity of the game. "Expel the Major!" was a cry heard around the League.

Undaunted, McLaughlin vowed to ice his five Americans and accomplished this against a Bruins team bent on smashing the upstarts into pieces. The Americans were prepared. They traded blow for blow with the Canadian-born Bruins and emerged with at least a draw in the body and stickchecking departments. But the scoreboard read: Boston 6, Chicago 2.

Now the Black Hawks had to take this all-American show to Canada, where their next game was at Maple Leaf Gardens against the Toronto Maple Leafs. This time they virtually were the equal of the more experienced home team and appeared capable of at least a tie. However, Toronto won the game 3-2 and the critics continued to carp. Lester Patrick, manager of the New York Rangers, denounced the American Black Hawks as a bunch of amateurs. As it happened, their next game was at Madison Square Garden against the Rangers.

When the ice had cleared, the final score was Chicago 4, New York 3.

That did it. The Major now was convinced that his plan had merit. What did it matter that the New York Americans (9-4) and Bruins (6-1) had routed his team in the final two games of the season? He ordered his scouts to find more American-born skaters, then executed the ultimate blow, hiring an American-born coach.

It was none other than Bill Stewart, the baseball umpire from Massachusetts who was one of the most accomplished referees in pro hockey. Stewart was aware of McLaughlin's all-American antics and didn't mind them, but also knew that the Major would fire a man as quickly as he'd hire him.

When McLaughlin offered him a one-year contract, Stewart laughed. "When he finally agreed to a two-year contract," Stewart said, "I also demanded the assurance from him that I would be the boss of the team and nobody else. He agreed to that too."

Stewart also agreed to add more Americans, among them Elwyn "Doc" Romnes from White Bear, Minnesota, and Cully Dahlstrom from Minneapolis, Minnesota, and went about the business of molding a competitive, if not a championship, hockey club.

Chicago finished third in the American Division and clinched a playoff berth, although remaining a distant 30 points from first-place Boston. Nevertheless, a playoff position was considered triumph enough since nobody expected Chicago to go anywhere in the postseason.

The Montreal Canadiens confronted the Americanized Black Hawks in the best-of-3 first round. The Canadiens won Game 1 6-4 at the Montreal Forum.

The second game was played at Chicago Stadium and there, in the friendly confines of the West Madison Street rink, Karakas backstopped a 4-0 Black Hawks victory.

Now the series shifted back to Montreal for the third and final game. After three periods the score was tied 2-2. The teams battled back and forth until seconds before the clock reached the 12-minute mark of overtime. Lou Trudel, a Black Hawks forward from Salem, Massachusetts, took a long shot that bounced off teammate Paul Thompson and into the Canadiens net. The Black Hawks won the series and advanced into the semifinal round against the New York Americans.

Once again Chicago would have the benefit of home ice only once in another best-of-3 series. New York won the opener at Madison Square Garden, but when the series shifted to Chicago it was none other than the American-born Dahlstrom who scored the winning goal for Chicago at 13:01 of overtime. The final score was 1-0 and Karakas had his second shutout in five playoff games.

New York was favored to capture the series in the third game at Madison Square Garden. But the Black Hawks had become known as a team of destiny and reinforced this theory by winning 3-2 on a third-period goal by Romnes.

The Americanized Black Hawks had pulled off a medium-sized miracle and faced the Maple Leafs in the Stanley Cup Final. By any standard of comparison the Black Hawks had to be regarded as underdogs. The Maple Leafs had finished first in the Canadian Division with 57 points while the Black Hawks were third in the American Division with 37.

That wasn't all. In leading his team past the Americans, Karakas had broken his big toe and was unable to lace his skates against the Maple Leafs. Unfortunately, he wasn't aware of the seriousness of his injury until game time and the Black Hawks were without a spare goalie.

Several goaltenders were available in Maple Leaf Gardens but the Toronto brass rejected all requests for assistance. Finally, in a rare stroke of luck, a Chicago agent discovered Alfie Moore, a minor-league goaltender who was considered so inept that the Maple Leafs agreed to allow him into the nets as Karakas' replacement.

It was an egregious mistake on the part of the Maple Leafs front office because Moore repulsed their attack except for one shot, and the Black Hawks won the game 3-1.

By now the Black Hawks had unearthed a goalkeeper from their own system, Paul Goodman, who played Game 2 but the Black Hawks lost 5-1. Stewart realized there was only one goaltender who could steer his crew to triumph and that was Karakas. The problem was how to work him into playable condition.

The Chicago medical staff devised a protective shoe that would adequately cover Karakas' broken toe. He was pronounced fit to play in the third game at Chicago Stadium and the Black Hawks won 2-1 before 18,496 roaring fans, on goals by Carl Voss of Chelsea, Massachusetts, and Romnes.

Leading the best-of-5 series 2-1, the Black Hawks needed one more win to bring Chicago its first Stanley Cup victory.

With the American-born Stewart behind the bench and the American-born Karakas in nets, the all-Canadian Maple Leafs didn't have a chance once the puck was dropped for the opening faceoff. Harold "Mush" March, Jack Shill, Dahlstrom, and Voss scored for the Black Hawks as they won 4-1. Bedlam reigned in cavernous Chicago Stadium and soon a chant hurtled down from the balcony, "We Want the Cup! We Want the Cup!"

But there was no Stanley Cup to present to the victorious Black Hawks. NHL President Frank Calder had ordered the championship trophy consigned to Toronto on the advice of friends who assured him that any team that iced eight American-born skaters could not possibly win the Stanley Cup.

Alas, Calder would have been better served, and justice would have been done, had the League president listened to the brains behind the All-American idea, Colonel Frederic McLaughlin.