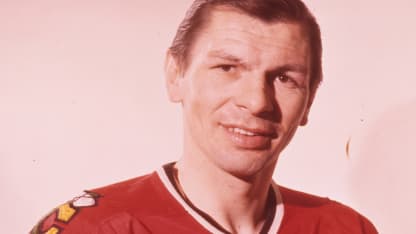

This is the first of a three-part written obituary series by Team Historian Bob Verdi on Stan Mikita, who passed away on Tuesday, Aug. 7.

Stan Mikita, a Hall of Fame center who played his entire career with the Blackhawks, has died. He was 78.

A transformational figure in hockey history, Mikita retired in 1980 after 22 seasons with the Blackhawks. Still, his resume shines. Mikita is the all-time franchise leader in points (1,467), games played (1,394), assists (926), and with 541 goals ranks second only to Bobby Hull.

Mikita remains as the only player in National Hockey League annals to earn the Art Ross, Hart and Lady Byng trophies in consecutive seasons (1966-67 and 1967-68). He also won the Art Ross as the league's leader in points in 1964 and 1965. Mikita contributed 11 points in 12 games toward a Stanley Cup in 1961, was a first team All-Star six times, and was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1983.

FEATURE: Remembering Mikita Part I - A Young Life Changed

Team Historian Bob Verdi writes about the late Stan Mikita in a three-part series

In 2008, Mikita was named a Blackhawks ambassador. Three years later, statues of Mikita and Hull were unveiled beside the United Center, recognition of what Mikita termed "the incredible life I have been so blessed to lead."

Decades before globalization in the NHL as we now know it, Mikita arrived via a serpentine path rife with fears and anxieties. He was born Stanislav Gvoth in Sokolce, Czechoslovakia. Father Juraj was a maintenance man in a textile factory; mother Emilia raised vegetables to feed the family behind what Mikita referred to as a "bungalow with two small rooms."

World War II was on, and Mikita said, "I vaguely remember German soldiers coming through our village." By the time Stan was 5, the conflict had ended, but not the stressful living conditions. As he recalled, "I really didn't understand Communism until I escaped from it." That journey began when his aunt and uncle, Anna and Joe Mikita, who had left Czechoslovakia years before, visited from their home in St. Catharines, Ontario.

Joe was brother to Stan's mother's. He and Anna had no children, but they suggested bringing one of the Gvoth's youngsters back to Canada. To afford Stanislav the chance at a better life, his parents agreed. At age 8, thinking that he was merely about to embark on a short trip, Stanislav and his niece, Irene, boarded a ship in France bound for Montreal.

Upon arriving in St. Catharines a few days before Christmas 1948, adopted Stanislav Gvoth became Stan Mikita. He referred to Anna and Joe as his mother and father and marveled at the surroundings - electricity, a refrigerator, a place to sleep instead of four to a room. But Stan was still homesick. He remembered imagining that every plane he saw flying above was the one that would return him to Czechoslovakia.

Eventually, Stan began playing road hockey with neighborhood kids. Some of them were cruel, calling him a "DP" or displaced person. He couldn't speak English, but he was competitive and talented. When Stan was 9, he signed up for a hockey league restricted to boys 10 to 12. He was initially rejected, but when enrollment was slow, Stan joined. All he needed was to acquire a pair of skates and a crash course in how to use them.

In time, Stan began playing bantam hockey, and with a chip on his shoulder. He was small. He had to have an edge. The Blackhawks, a forlorn franchise, coincidentally had developed a sponsorship with the St. Catharines Teepees, a junior team. The Blackhawks had their eye on this raw kid, but the Teepees' coach, Rudy Pilous, implored Stan to straighten out, or there would be no tryout. Be a player instead of a punk. Stan, who had cracked the language barrier by then, comprehended the message. That window to a new and better life, sought by his parents when they grudgingly let go of him, was now coming into focus.

"If you had written a script and tried to sell my story to a director for a movie, he'd have laughed at you," Mikita wrote in his autobiography, "Forever A Blackhawk," published in 2011. "Not believable enough. Kid leaves Czechoslovakia at the age of 8, can't speak a word of English, winds up living in a hockey hotbed like St. Catharines, is just dumb enough to hang out with a bad crowd but just smart enough to realize that he has to break away, and becomes good enough to earn a living by playing a game he loves. Crazy.

"If I hadn't left Czechoslovakia, I probably would have joined the army or maybe the Communist party or, with my attitude, been sent to Siberia. My mother, Emilia, came to the United States several times and saw the lifestyle I enjoyed in Chicago with my wife, Jill, and our wonderful children. Shortly before she died in 1996, Jill and I were visiting her in her home. I recall one instance when Mom became quiet and very pensive. She was quiet, thinking, pondering. Then she just looked up at me and, out of nowhere, said, 'I made the right decision.' As I look back at the amazing series of events and consequences that shaped my life, I scratch my head and give thanks."